Fry Bread Is…

Fry Bread Is Food

I am a food guy. I eat a lot of it, of course, and I write about it–I’m not going to win any awards for my writing, but I like to think I do a pretty good job of communicating the essence of enjoying a sandwich. If nothing else, I certainly do my best to enjoy every sandwich.

I do not feel qualified though, not really, to write about frybread. It is a complicated subject, a legacy of some of the more shameful moments in our nation’s history. My understanding of these events comes from an outsider’s perspective and as such it is flawed.

Why, then, Jim, is this the longest article you’ve ever written on this site? SHUT UP, VOICE OF REASON!

(Let that be fair warning to you though. This post was months in the making. It meanders, covering a lot of ground but without making much of a point. Perhaps that is also true of the site as a whole, but nowhere more so than here)

I’ve borrowed not only ideas but also the headings of this article (though somewhat mixed up and out of order, of necessity and with my apologies) from a stunningly beautiful children’s book on the subject called Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story. Like many of the great children’s books, it uses simple but evocative words along with its eloquent illustrations to bring about in the reader a feeling, of warmth, of belonging, of family.

It is an important book, a beautiful book, and I’m glad to own it despite no longer having any children of an age that would appreciate picture books like this one. Reading it has informed this post greatly. All tasting notes, however, are my own.

Fry Bread Is Us

My own family connection to frybread is of course less deep than that of the book’s author. In Illinois where I grew up and where I have lived my entire 50 years of life, we have no Federally-recognized Native tribes, no reservations, no pow wows or wacipis, no living Native American history to draw on. We have instead the Black Hawk Historic Site, the Albany Mounds, the Cahokia Mounds. Apart from finding the occasional stone arrowhead on a hike, all we see of Native American culture are the dusty, curated memories we’re shown on school trips.

It was my wife Mindy, a native of Eastern Washington, who first made frybread tacos for me. Frybread was a dish she’d been introduced to by her parents as a child. Native American reservations and the living indigenous culture they represent are more prevalent in the northwest than this part of the Midwest, and frybread is a more broadly adopted dish there.

The only real family history I have centered around frybread is the story my brother just reminded me of last week. When I turned 29 I asked for frybread tacos for my birthday dinner. Mom was hosting, and she was not familiar with them but was willing to give it a try. Unfortunately, she happened to run out of cumin that day and someone–I don’t remember whether it was Mom or me–had this brilliant thought: hey, you know what has a lot of cumin in it? Curry powder!

Curry powder makes for a memorably strange picadillo. I can’t say I recommend it necessarily, but I can say that I enjoyed that birthday, and every birthday I get to celebrate with family. In any case, this is the depth–or lack thereof–of my own family history with frybread. It does not, cannot compare to the experiences of Native Americans.

Fry Bread Is History

At first this item was in our List as “Navajo fry bread,” because that it what we called it when Mindy first started making it for me. According to most accounts, it was the Navajo tribe who originated it. In the 1860s, groups of Navajo were relocated by the US Army from their homes in what is now eastern Arizona and western New Mexico, forced to march hundreds of miles to an area around Fort Sumner in eastern New Mexico. This became known as the Long Walk. The traditional Navajo methods of agriculture were unsuited to the new location, and as a result they were forced to subsist on US Government-supplied staples of flour, sugar, and lard.

However, frybread knows no nation among Native Americans, not really. There are nearly 600 Federally-recognized Native American tribes and over 300 Federal reservations in the United State. There are numerous State-recognized Native American lands, communities, and “statistical areas” as well. There is nowhere in this country where Native Americans did not once live long before Europeans arrived. Whether on a reservation or in a statistical area or in a town with non-natives, whether they honor and observe their heritage, in most of those places, Native Americans or their descendants are living still. In many of those indigenous families, frybread is a way of life.

Fry bread is served at various Native American nations’ Pow Wows, Wacipis, and festivals in the Midwest, the Northeast, the Northwest, and the Southwest; in Oklahoma, in Montana, in Nebraska, in Minnesota, in New York. Sometimes it may be called Navajo frybread. But almost everywhere you see it, the name used is the more general, and historically inaccurate, “Indian Fry Bread.” I chose to use “Native American Frybread” in our List, but Indian Fry Bread, accurate or no, sensitive or no, is a name as ubiquitous as the food itself.

Fry Bread Is Art

Fry bread is having a bit of a moment, culturally. Starting in early August, streaming TV service Hulu released the first episode of a new show called Reservation Dogs. Developed by FX Network, the show centers around 4 teenage Native American kids living on a reservation in Oklahoma. They get in fights; they get in trouble; they inhabit a world rich with characters and a culture that has its own assumptions.

I’ve only just started watching the show this week, but I’m already quite charmed by it. One of the things I enjoy most about the show is that it does not handhold the viewer through the day-to-day aspects of reservation life. Nearly every episode, I find myself googling some reference that escapes me that these characters take for granted–the keen and outsized interest in venison backstrap, the terrifying nature of owl eyes, who or what is the deer lady. Based on the accuracy with which autocomplete finished my questions for me, I haven’t been the only one asking them.

Reservation life as depicted in the show is filled with these rich textural details added by the indigenous writing team. The unforced chemistry of the central 4 teens is matched by a terrific extended cast. I don’t know reservation life in Oklahoma, at all, but the show’s deliberate pace, boredom-induced teen mischief, family dynamics, the missing friend whose still loss looms over them after a year–all of it feels very genuine.

Frybread doesn’t really turn up much in the first few episodes of the show–an item on a menu board at a restaurant where everybody orders the catfish instead. Then came episode 4, kicked off by the “Greasy Frybread” rap video that has been making the rounds on social media (which is where it was brought to my attention by a friend–you know who you are) ever since.

This may in some manner have contributed to a recent rash of new blog posts about fry bread. As for the Tribunal, we’ve had Frybread on our schedule for some time now, and today it’s our turn.

Fry Bread Is Place

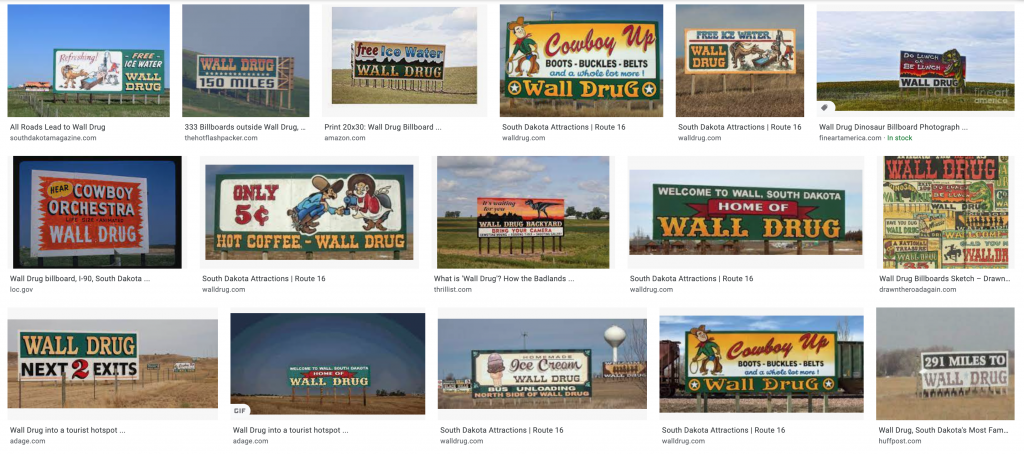

Fry bread was named the State Bread of South Dakota in 2005 and is still considered one of the official symbols of the state. Driving West across South Dakota can be monotonous. For hundreds of miles the state, like Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, and a stretch of Canada, is part of a mind-numbingly flat grassland we in the US call the Great Plains. Interstate 90, the primary East-West conduit through the state, can and does go miles and miles without even a mild curve due to the lack of natural obstacles. The main entertainment on the long drive West through South Dakota consists of reading the increasingly grandiose promises printed on the innumerable billboards imploring you to visit Wall Drug (free Ice Water!).

And you should by all means visit Wall Drug (HOT COFFEE only 5¢). If you look hard enough, you might even find the actual drugstore, squeezed in amongst rack after rack of kitschy memorabilia. But don’t stop there. Just south of Wall Drug (HOMEMADE ICE CREAM) lies some of the most breathtaking, ruggedly broken terrain in the United States, in Badlands National Park.

Jagged buttes jut from surrounding grasslands, the canyons eaten into the rock by erosion laying bare millions of years of geological history. Clearly visible layers tell the story of the inland sea that once covered this area of the continent; of how and when that inland sea drained away; of the hot wetlands that took its place; of the grasslands it eventually became.

Fry Bread Is Time

Last August, the five of us (and our dog) drove to eastern Washington for a mini family reunion with Mindy’s parents and her brother’s family. We drove long days on the way out there, barely even stopping at Wall Drug (Homemade Donuts), in order to spend a full weekend amongst family. Then we took it slow on the way back, enjoying the dying pastime that is the family road trip, spending time together exploring the oddities we encountered. We stopped at random roadside stands, drove miles off course to visit waterfalls and other scenes of natural beauty, and eventually hit most of the roadside attractions that the long straight stretch of I-90 through South Dakota had to offer.

It was during this trip that we first discovered a little piece of heaven tucked away in the backroads behind Badlands National Park, a tiny motel/campground/RV park in the even tinier town of Interior, South Dakota.

Interior is not a big place–the business district that sign in the background is pointing to consists I believe of 3 bars and a small grocery store. During the first full week or so of August, a well-known motorcycle rally pulls attendees from around the country, filling up every hotel and campground in a broad radius around the town of Sturgis, South Dakota. We were unaware of this when we booked the room, but the Badlands Motel & Campground in Interior, 103 miles from Sturgis, was the only place in the area with a vacancy on a Tuesday in early August, even booking months in advance as we did.

It was a stroke of luck for us–and I mean this in all sincerity. I find it hard to explain what it is we like about this place so much. A plain description comes across too prosaically, but it isn’t fair to the town to get hyperbolic with superlatives either. Interior is extraordinary in some ways and very ordinary in others–but even the ordinary parts feel great to us.

Interior is situated smack dab in the middle of the badlands. On that Tuesday when we first checked in, we asked Google for directions while we were in the middle of the “Badlands Loop,” a scenic byway through the National Park that showcases many of its more fascinating vistas. Google’s route had us immediately turn off the loop and onto a gravel road. 3 miles later, that road became Interior’s Main Street. 3 blocks after that, we emerged on the far end of town and arrived at the motel.

The views around the campground are nothing short of spectacular. During our stay the campground’s population, made up largely of bikers who’d traveled here for Sturgis, had grown to seemingly exceed that of the town. Yet in contrast to the rally itself, the campground was extraordinarily quiet. Peaceful. Restful. There was something about it, a stillness, that was wholesome, even healing.

Needless to say, we really enjoyed our brief stay in Interior, SD and were looking for an excuse to return. When I initially began researching frybread a few months ago I learned that it was the “official bread” of South Dakota. I also discovered that the Oglala Lakota Nation in the Pine Ridge Reservation just south of Interior was planning a Wacipi in early August of 2021, almost exactly one year after our first visit. That decision was almost too easy to make.

It was *not* easy, however, for us to book an actual room at the Badlands Motel & Campground the first weekend in August. That weekend would be during the initial days of Sturgis, and the motel was entirely full for the duration. The campground still had openings, though, and we were able to reserve an air-conditioned cabin for the weekend.

A week or so before our planned trip, we learned that the Oglala Lakota Wacipi had been indefinitely postponed. It was a disappointment, but surely an understandable move on their part. We elected to continue with our trip as there were plenty of other things to see, and if nothing else, we just wanted to spend more time in Interior.

Fry Bread Is Flavor

The gas station next door to the campground sells homemade roast beef sandwiches during Sturgis. The rest of the year they offer a different menu daily but during the rally roast beef is all you get–a simple, shredded pot roast type beef, served on a hamburger bun with barbecue sauce and/or horseradish. It’s nothing spectacular, but good enough that it sells out early every day. The bars in town serve standard bar fare–bar pizzas, burgers, steak sandwiches, fried cheese, macrobrewed American lagers, the occasional mass-market “craft” beer like Goose Island IPA. The campground itself serves breakfast in a small dining area off the front desk and gift shop area. They offer a choice between pancakes and sausage or biscuits and gravy, easy foods to churn out in bulk and feed a crowd. Again, there is nothing really outstanding or unique there. But even very ordinary things somehow taste better than they should in that place.

On the way to Interior, right on the Badlands National Park scenic byway, next door to the Visitor Center and just before the turnoff to Interior, there is another combination motel and campground called Cedar Pass Lodge. This motor inn also has a gift shop, somewhat larger than the one in Interior, complete with a medium-sized “family dining” type space simply named Cedar Pass Restaurant. On the menu at Cedar Pass is a “Sioux Indian Taco” that topped the website travelsouthdakota.com‘s list of the best frybread tacos in the state.

Cedar Pass was a high-value target for me on this trip, and I wanted to stop there as early as we could. I called ahead when we were still about an hour down the road and found out that 1) there were picnic tables outside, so we’d be able to eat there with our dog if we ordered to go, and 2) the restaurant closed at 7:28 pm.

“7:28? That’s awful specific…”

“Well if I tell people 7:30, they want to come in and order something right when we’re closing!”

So we hurried up and arrived with time to spare–6:45 or so, anyway–grabbed a picnic table, and ordered a couple of their Indian tacos to go.

The frybread taco I had at Cedar Pass Lodge that day was the first I’d had in South Dakota. I couldn’t call myself any kind of a local expert just yet. Still, 2 bites in I was already calling bullshit on that “best in the state” article. The toppings were fine, standard frybread taco fare–ground beef (or in this case “bison”), shredded iceberg lettuce, a shredded cheese blend, salsa from a jar, black olives from a can. The toppings though were not the issue.

The travelsouthdakota.com article claimed that the frybread there is made fresh daily. Had this frybread been made sometime that day? Sure, probably. What time that day? I don’t care to speculate, but I’d guess that it had spent a good few hours sitting under a heat lamp or in a warming oven before being served to me. It was on the cool end of lukewarm and bordering on stale, soft where it should be crisp and brittle where it should be soft. That’ll teach me to show up just before closing time I guess.

Fry Bread Is Nation

We had planned on spending our Saturday in South Dakota attending the now-postponed Wacipi. With the Wacipi on hold, we decided to educate ourselves by visiting a few Native American memorial sites in the area. First thing after a breakfast of biscuits and gravy at the campgrounds, we drove south into the Pine Ridge Reservation to see the Wounded Knee memorial.

At the reservation’s boundary, we were greeted by a checkpoint, with a few members of the Oglala Lakota Nation questioning us about our Covid-19 status before we could continue. It was a sensible precaution I thought, and not terribly intrusive. The three of us were fully vaccinated and in good health, so we answered a few questions and continued without much delay.

Wounded Knee, South Dakota is about a 75 minute drive south of Interior–practically next door by the standards of that area of the country. Upon arrival to the nearly-empty parking lot we were greeted by an older model car roaring up from a vantage point a quarter mile away. An elderly lady dismounted, opened her trunk, got out a box, and launched into a sales pitch, showing us a collection of necklaces she’d made. As we negotiated with her another, younger lady got out of the only other car in the parking lot and showed us her necklaces as well. A reservation policeman watched stoically from a marked SUV nearby. Mindy picked out a turtle necklace and I picked out a dreamcatcher and we left the conversation about $40 lighter.

Were they real, handmade Native American art? I don’t know, and I suppose it doesn’t really matter. Both of them are beautiful; both hang from the rearview mirror in our car as good luck charms. We’re happy to have them, and glad to have made a small contribution to the community by buying them. There was otherwise no entry fee, no donation asked to visit the memorial.

The memorial itself is a simple but somber experience consisting of two parts. First, in the parking lot there is a large two-sided sign telling the story of the final days of Chief Big Foot and the band of Lakota and Sioux that were massacred there in December of 1890. Second, a short walk away atop a nearby hill is a memorial where the mass grave was dug for the fallen–an arch, a fence bedecked with brightly-colored cloths, graves and a standing stone we dared not approach closely with our dog. Barebones to say the least, but educational.

On the other end of the roadside attraction spectrum, there is the Crazy Horse Memorial in the Black Hills, an in situ sculpture-in-progress carved directly into the side of a mountain. When it is completed it will depict the Oglala Lakota war leader on horseback, extending an arm to point to his homeland.

To reach this monument deep in the Black Hills, first one drives past mile after mile of Wisconsin Dells-style tourist traps (Reptile Gardens! Bear Country, USA! Cosmos Mystery Area!), Mount Rushmore, lodge after lodge, winery after winery, brewery after brewery, a solid hour of nonstop yeehaw Western capitalism. Upon reaching the site, one pays a fee to park at the visitor center/museum/gift shop/restaurant, and another fee to take a bus to the monument. We could not take the bus with the dog, and walking directly to the monument was apparently not permitted, so we milled around the gift shop area for a while looking at statues before driving away.

The mountain carving is an impressive enough sight, and I’m glad to have visited it this time instead of another trip to Mount Rushmore, but I have no desire to return (unless somehow it gets completed in my lifetime. That would be something to see!)

Fry Bread Is Sound

55 miles north of the Crazy Horse Monument–not far by South Dakota standards, but nearly 90 minutes drive through the winding backroads of the Black Hills–at the head of Spearfish Canyon, lies a roadhouse called Cheyenne Crossing. Between the indoor cafe, the outdoor beer garden, and the attached shop, it seems like it might be a nice place to visit under normal circumstances.

Sturgis makes the circumstances in early August anything but normal. The entire property is carpeted, wall-to-wall, in bikers and their bikes, and there is a constant thunderous roar of motorcycle engines both from those at the roadhouse and from the groups of motorcycles entering and exiting the canyon’s scenic drive. When we arrived on the afternoon of Saturday, August 7th, it was considerably more crowded than in this August 5th photo taken from Cheyenne Crossing’s Facebook page.

I hadn’t reckoned with all this noise when planning the day’s outing. Yet Cheyenne Crossing was another of the places cited as having one of the best Indian Tacos in the state. We were here, and we were hungry. We couldn’t eat inside because we had the dog with us. We couldn’t eat outside because of the crowds and noise. We could, however, get some frybread treats to go and make a picnic a few miles downstream along the Spearfish Canyon road.

It doesn’t look like much, I know. On the surface it doesn’t even look as good as the Indian Taco from Cedar Lodge had been. Appearances can be deceiving though. The short drive down Spearfish Canyon to a suitable picnic spot hadn’t done the dish any favors–the sour cream, initially deposited in a neat scoop in the center, had slid off to the side, as had the salsa and some of the other toppings. Believe me when I tell you that this was head and shoulders above the Cedar Lodge offering.

Why? Entirely on the strength of the fresh, hot frybread. It remained relatively crisp-edged despite the toppings, despite steaming in that styrofoam container for the 10 minute drive. The toppings themselves were comparable to what had been served at Cedar Pass Lodge, with slight differences–thinner shreds of cheese, red onions, a slightly different salsa, hand-torn lettuce. The superior frybread made all the difference though.

Cheyenne Crossing also offers a few dessert versions of frybread, including this simple presentation; hot, crisp frybread, lightly dusted with confectioner’s sugar, served with a small dish of local Black Hills honey on the side to be drizzled on each bite. Not one scrap of this went to waste; the crisp edges were highly contested, but even the soft, moist interior was prized and devoured. The frybread shell was thick but light–chemically leavened I suspect rather than yeast-raised, so not as light as, say, a glazed donut would be, but not dense and crumbly like a cake donut either. It does seem well-suited to desserts, and they serve a frybread sundae as well (which I’m glad I did not order, as it would not have survived the drive).

But I prefer savory treats to sweet ones, generally, and the large-sized frybread taco from Cheyenne Crossing was enough to feed the three of us as we picnicked in the in the roadside greenery, the constant dopplering rumble of passing motorcycle engines drowning out the rush of the nearby Spearfish Creek. Spearfish Canyon is a spectacular drive, an even better place to stop and look around a while, but a bit of a skull-rattling echo chamber for motorcycle engines.

Fry Bread Is Shape

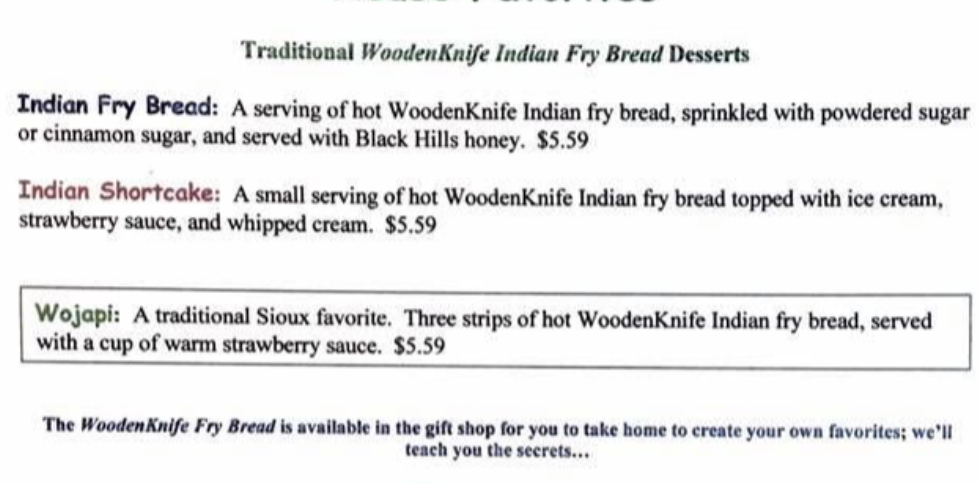

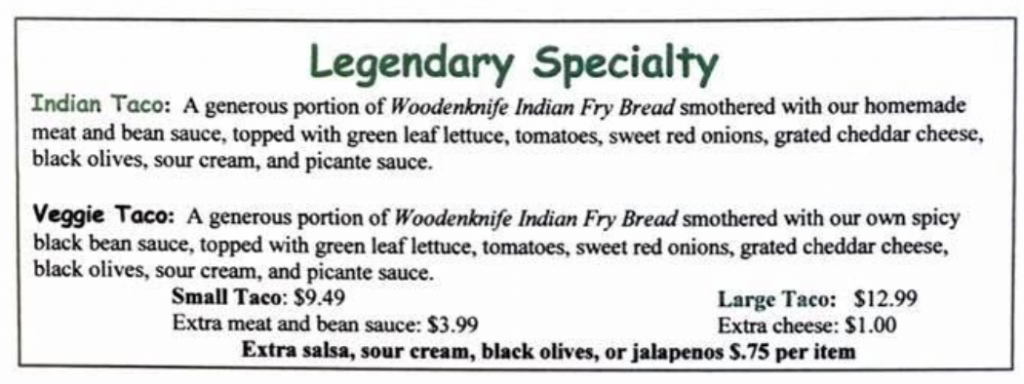

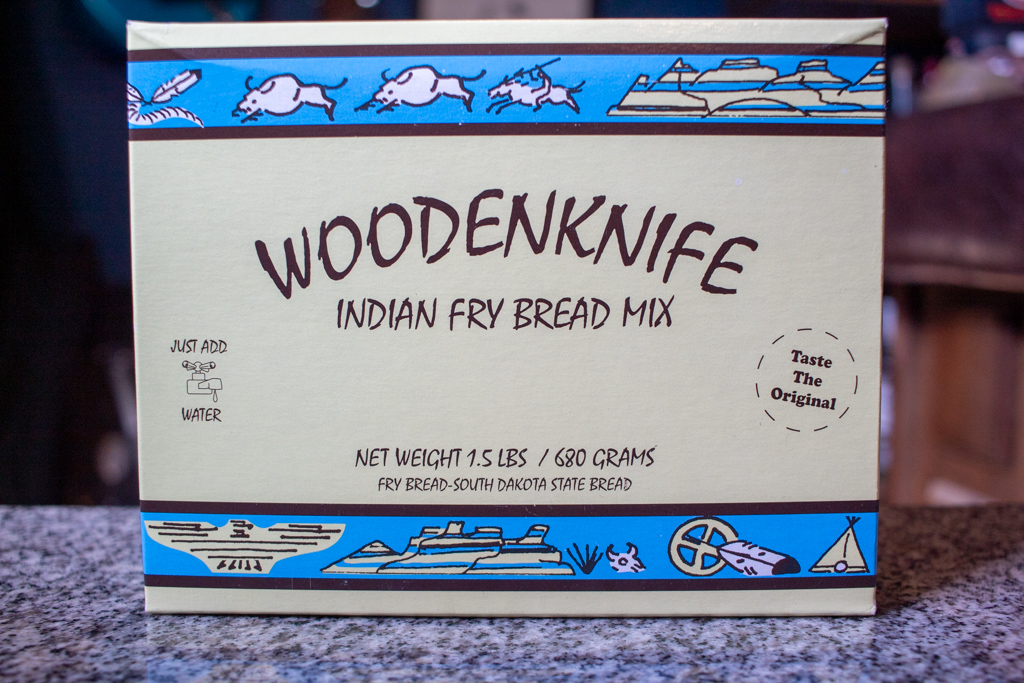

Did you notice the WoodenKnife Indian Fry Bread reference in the above menu snippet? I did. Here it is again in the menu’s writeup of their Indian Taco.

The WoodenKnife Company, makers of Cheyenne Crossing’s delicious fry bread mix, is headquartered in–get this–Interior, South Dakota, our new favorite little vacation spot. Per the History page on their site…

Before there was a WoodenKnife Company there was the WoodenKnife Cafe in Interior, which has a view of the Badlands of South Dakota. At the cafe their specialty is authentic Indian tacos made from a special fry bread recipe. After sampling the delicious fry bread, tourist and locals alike encouraged Ansel WoodenKnife to market the Indian Fry Bread Mix.

Google Maps puts the address listed on the website just south of Interior proper, a few miles past the Oglala Lakota Nation checkpoint and into Reservation territory. We drove past it and… there’s something there. From the road, it looks like any other Ranch in that stretch of the Dakotas. It doesn’t look like the site of the original WoodenKnife Cafe, or of a plant churning out boxes and sacks of frybread mix, however artisanal the product, however lovely the packaging.

I wasn’t able to speak with the folks at Wooden Knife, though I’d have loved to. I’m not sure where the Cafe was originally located, or where they make their mix today. I was however, able to get hold of some of that mix. (It wasn’t hard. They sell it on Amazon.)

The mix instructions call for using 1 1/2 cups of water per box of mix, saying that the dough will be slightly stiff but should not require kneading, only stirring with a spoon. I found the dough a little too shaggy at that hydration point for spoon work but digging in with my hands I was able to get it to come together. After that, the dough should be rested for 30 minutes before using.

And how do they recommend shaping the dough? “Roll or pat to about pancake thickness. Cut into desired size and shape, and drop into hot oil.” Cut it–with a cookie cutter? A biscuit cutter? Call me a glutton but I like my frybread a little bigger than that. Besides, I don’t need it to be perfectly round.

When rolled out fairly thin, the frybread starts with a mostly round shape and a uniform thickness. Once the dough hits the frying oil though, the leavening process kicks into fast-forward. Pockets of gas form, extruding bubbles of varying size and shape. Sometimes the entire bread inflates like a mylar balloon, leaving a hollow interior. Other times, alien landscapes form in the dough.

This method of shaping allows you to create a wide, flat piece of bread well-suited for taco toppings, with plenty of surface area that browns nicely in the hot oil. The resulting bread is thin, though. Even where it seems thick that is an illusion, with only air inside. It’s all crisp surface and no fluffy interior, all crunch and no chew.

If instead you roll the bread into a ball between your hands, then use your fingertips or knuckles against a hard surface to spread it into a thick round shape, you get something more like the bokit of Guadeloupe that we wrote about last year–a thicker, rounder bread, perhaps with a large pocket of air in the middle but plenty of bread crumb as well.

Fry breads shaped like this don’t hold toppings very well–the tops are rounded and the toppings slide right off. They are great for eating out of hand though, on their own or as a bread roll with a soup or stew. You could even slice them open and put sandwich fillings in the middle I suppose. None of those would be a frybread taco, but they’d be delicious anyway.

Instead of pounding or rolling, you could instead stretch the frybread dough, like a pizza crust or, more accurately, like a Hungarian lángos, another fried flatbread we covered recently. Using this technique, you can leave your bread relatively flat and thick, like above, with a crisp outer crust yet plenty of soft chewy crumb inside.

Alternatively, you could stretch it out wider and thinner, leaving a thicker rim around the edges, much like the cornicione of a pizza crust. This gives you a combination of thin crispy bits and thicker, fluffier bits and leaves the frybread flat enough to support plenty of taco toppings.

There isn’t really a wrong way to shape frybread. No two of these frybreads were the same, yet all of them were excellent–the bread made from WoodenKnife’s mix rises well and consistently and tastes quite good, slightly sweet, not terribly salty. I’ve come to prefer the methods done by hand though, without the rolling pin. They are more prone to introducing imperfections in the shape of the frybread. Those imperfections in the bread are the best parts.

Fry Bread Is Color

The WoodenKnife box has printed on it a recommended recipe for a frybread taco meat topping. It is a combination of ground beef, refried beans, onions, tomato sauce, spices, and just a little taco seasoning mix from a packet. The recipe makes a thick meat sauce that is very much like the kind of condiment chili you might put on a hot dog or burger. The box also recommends serving this meat sauce as if it were chili, in a bowl, with frybread on the side for dipping. I am less enthused about this recommendation. Condiment chili does not make a good chili for eating, and vice versa.

It does make a terrific taco filling though–or topping, when it comes to frybread tacos. Along with thin shreds of yellow-green iceberg lettuce; ripe, deeply red tomatoes from our garden; a shredded mix of both yellow and white cheeses; the bright green color and flavor of chopped cilantro; a smattering of black olives; a brilliant white crown of sour cream and an orangish-red spiral of picante sauce (OK it was actually Taco Bell Fire Sauce. I buy it by the case and I am not ashamed.), it made one hell of a good frybread taco.

I am not a fan in general of presliced black olives from a can, and this taco didn’t change my mind on that score. Everything else worked though. The meat sauce had a viscosity from the refried beans that allowed it to stick tightly to the bread and glue the additional toppings in place as well. It was a little bit salty from the taco mix and a little bit spicy from red pepper flakes, chili powder, and Louisiana Hot Sauce. That spiciness was nicely amplified by the fire sauce but then cooled by the sour cream. The citrusy brightness of the cilantro, the crispness of iceberg lettuce, and the sweet and savory wonder of fresh tomatoes right out of a garden all complement the savory meatiness of that sauce.

What could be better? Perhaps something fresher than my highly prized Taco Bell Fire Sauce. Perhaps in lieu of a taco sauce I could use freshly picked red and yellow tomatoes, ripe red jalapenos and serranos, and green onions and chopped cilantro and lime juice to make a kind of pico de gallo for topping the taco.

And maybe the protein could be more colorful as well. Reading as much as I have about Native American culture the past week or two inspired me to cook a kind of stew–a chili I suppose–using a combination of corn, squash and beans that is often cited as the cornerstone of many native cultures along with a collection of fresh vegetables from my garden. Look to a more authentic source than this site for a real recipe using the “Three Sisters” of Native American agriculture but this stew is delicious.

Squash, Sweet Corn, and Bean Stew

Ingredients

- 2.5 lbs butternut squash peeled, seeded, cubed

- 4 cobs sweet corn

- 1 can pinto beans undrained

- 1 can pink beans undrained

- 2 onions chopped

- 5 cloves garlic chopped

- 3-4 serrano peppers chopped

- 2-3 jalapeno peppers chopped

- 1 cubanelle pepper chopped

- 2 tbsp vegetable oil

- 1 tsp red pepper flakes

- 4 tomatoes diced

- 1 tsp cumin

- 1 tsp chili powder

- 1/2 tsp Mexican oregano

- 1 quart turkey stock

- 1 bunch cilantro leaves and tender stems, finely chopped

- salt and pepper to taste

Instructions

- Cut the sweet corn from the cobs. Discard or find another use for the cobs. Alternatively, use an equivalent amount (2 to 2 1/2 cups) of frozen sweet corn

- Heat the vegetable oil in a stockpot or Dutch oven. Add the red pepper flakes and stir for a minute, allowing the pepper flavor to infuse the oil.

- Add the onions, garlic, and peppers. Cook, stirring frequently, until the onions are softened

- Add the oregano, cumin and chili powder. Cook until aromatic, 1 minute or so

- Add the tomatoes and cook until heated.

- Add the squash, sweet corn, and both types of beans. Add the stock. Stir and heat to a low boil, then reduce heat and simmer until squash is tender and the stock reduces/thickens (1 hour or so)

- Add chopped cilantro and stir in. Season to taste. Serve

Notes

Naturally thickened by all three of its core ingredients, this stew also made a fine frybread taco topping. The white and yellow kernels of corn were crisp, sweet little explosions of flavor, maintaining their crispness despite the long stewing time. The orange chunks of butternut squash also had a mild sweet, nutty flavor. The meatiness of the pink beans and the creaminess of the pinto beans rounded out the stew nicely, and though I’d like to have added more chilies–I’m cooking for more people than myself alone so I err on the side of caution–there’s a nice little heat there. The stew was substantial enough to stand alone and thick enough to make a decent taco filling. That did not stop me from supplementing it with some shredded pork leftover from my family’s recent Labor Day Hog Roast though.

Crisp, green Romaine lettuce, sweet and savory tender red tomato, varicolored shreds of cheese and a white shock of sour cream almost entirely covered in red, yellow and green pico de gallo finished out this taco. It was too much, frankly, the massive hand-stretched bread covered in a mound of delightful and mutually complementary toppings.

So we’ve heard about the flavor of the meat sauce, of the stew. What about the frybread? What does it do for the dish? What is frybread?

Fry Bread Is Everything

Fry bread is crunch. Fry bread is chew. Fry bread is a source of calories. Fry bread is a full stomach. Fry bread is a taco shell. Fry bread is a scoop for chili. Fry bread is a sop for soup. Fry bread is a base for dessert. Fry bread is an edible plate. Fry bread is a frisbee? It could be I guess, but that would be a waste of good frybread.

Fry bread is all these things, and all the things in the headings of this post, and whatever else you want it to be. Jackstands for your car? If you fry that bread hard enough, yes.

Fry Bread Is You

If you made it this far, I applaud you. You must either be a huge fan of fry bread, or desperately starved for entertainment. Assuming it’s the former, please comment on the article and tell us your own experience with frybread. It’s almost certain to be more interesting than mine!

I like sandwiches.

I like a lot of other things too but sandwiches are pretty great

Recent Comments