Guadeloupe’s Bokit

In 1493, Christopher Columbus landed on a small island in the Caribbean, called Karukera by the Caribe people who lived there. Columbus landed just long enough to call the place Santa María de Guadalupe and then moved on looking for other resources for Spain to exploit. It was not the Spanish who eventually wiped out the locals and colonized Guadeloupe, though. In this case it was the French. The climate of the Caribbean is ideal for growing sugarcane, and it was not long before plantation farming and slavery were instituted to take advantage of it.

France has, with some notable exceptions, held territory in this area of the Caribbean ever since. Guadeloupe in particular has from time to time been occupied by other colonialist forces, and enjoyed a brief period of emancipation and self-rule during France’s own revolutionary period. However, in 1802 slavery was brutally reinstated, not to be permanently abolished by the French until 1848. This grouping of islands is still called Guadaloupe, and along with Martinique, Saint Martin, and Saint Barthélemy, make up what is now known as the French West Indies or the French Antilles.

As with many of the islands of the Caribbean, the population of Guadeloupe is largely descended from those African slaves, along with a mix of South Asian indentured workers, native people of the Americas, and the remnants of the European colonists. Still a French colony, or “overseas department,” French is Guadeloupe’s official language, but what is commonly spoken there is a Creole based on French, but containing elements of African Bantu, English, and Carib. The culture, too, is a melange–French architecture; a slower pace of day-to-day life more suited to the constant heat and sun of the tropical setting; celebratory Carnivale revels punctuated by African-derived drum music and dancing.

As we’ve seen with other cuisines developed in a sometimes violent clash of cultures, the food can be spectacular. Guadeloupe’s local foods–tropical fruits, citrus, tubers, native American vegetables, fresh-caught seafood–are to some extent used with French techniques and ingredients such as thyme, but in large part, the Guadeloupean culinary traditions have come from the African hands that worked the kitchens, that harvested the sugarcane and extracted its juices on the plantations, that processed the sweet sugarcane into Guadeloupe’s famous rhum agricole. Guadeloupean food is another creole.

Guadeoupe’s bokits are a type of fry bread derived from “johnnycakes,” a simple flatbread that has developed many variants around the Caribbean. The bokit, like many of them, is deep-fried in oil, but unlike many of them is a yeast-leavened bread made with wheat flour. These puffy fried bread discs are then sliced open, stuffed with any number of ingredients–local fish, shredded chicken, egg, ham and cheese, usually some type of salad–and served as sandwiches.

It appears similar in some ways to the Trini “bake”–a confusingly named fry bread that is also stuffed with ingredients like shark or saltfish to make a sandwich. We’ll be covering that one toward the end of our Phase 2 run, but Mindy and I snuck a taste at A&A Bake & Doubles Shop in Brooklyn last year.

As Guadeloupean food has not made it to the US of which I’m aware–please correct me if I’m wrong–and travel to the Caribbean is only a distant dream at this time, I would have to make the Bokits myself. Right away I found this page describing not only a recipe for the bread, but for several fillings as well, including conch, a type of sea snail recognizable by its large and distinctive shell.

A one-stop shop for recipes is inviting, but I kept looking, and I found a chicken recipe I liked better, and a saltfish recipe that might be a little easier, and I found a recipe for the bread that I had to translate from the French, so that must be a good thing, right? Eventually I had several types of bokit I wanted to try.

The bread recipe used an extremely low hydration ratio, something like 50%, which even with the addition of a tablespoon of lard I had to supplement with a few extra drops of water to even get the dough to come together. Once it did though, it was easy enough to work, and unsticky enough to roll out easily for frying.

Once that bread was in the oil, though, it was unpredictable. The oil sets the crust of the bread. But as the dough rapidly heats, the yeast, in their dying frenzy, go into a mad rage of CO2 production, causing the bread to expand just as rapidly. For some of the rolls, this meant that crust would split, creating patterns similar to those cut into the tops of bread loaves with a baker’s lame. For some, the CO2 found a hole and created a jet engine for the roll, spattering oil and propelling the dough in a circle until the bread was flipped over or removed. Some of them simply blew up like balloons.

When I cut them open most of them, whether they’d superinflated or not, had a big hollow center, perfect for stuffing with a filling.

For my first run at these, I’d prepared 3 filling types. First was a shredded roast chicken, roasted using a Guadeloupean seasoning called Colombo powder. This is a type of curry powder that came to the Caribbean with a group of Sri Lankan indentured laborers brought there in the mid-19th century after the abolition of slavery by France. The recipe involved making a paste of the powder along with other spices, onion, garlic, and oil, and spreading it under the skin of a whole chicken directly against the meat before roasting at a high heat over a layer of water until cooked through. The water keeps the dripping chicken fat from burning and smoking, and elevating the chicken above the water keeps the chicken from losing too much of the rub’s flavor. Still, once it was cooled down a bit and shredded, I added some more lemon juice and Colombo powder to liven up the flavor a bit.

Second was conch, a bokit filling that fascinated me but for which I was able to find few recipes. I worked off of the recipe provided by the Ketty Kreyol site, starting by cooking the whole conch in a pressure cooker for 45 minutes to help make it more tender. I did not, however, finish by shredding the meat in a food processor. I simple diced it up and sauteed it with onion, garlic, parsley, and thyme. The meat was sweet, like crab, but with a chewier texture more akin to squid or, I suppose, snail.

Finally, I had prepared saltfish as well. This salted, dried cod was soaked overnight, with several changes of water, and then gently poached for 15 minutes before being simply shredded with a fork.

I started with the chicken. Filling the hole on one side of the bread roll with chicken and the other side with shredded lettuce, I finished the salad side with a tomato and some thin slices of red onion. I finished the meat side with sauce chien and some Matouk’s hot pepper sauce, a Caribbean favorite.

What is Sauce Chien? A digression

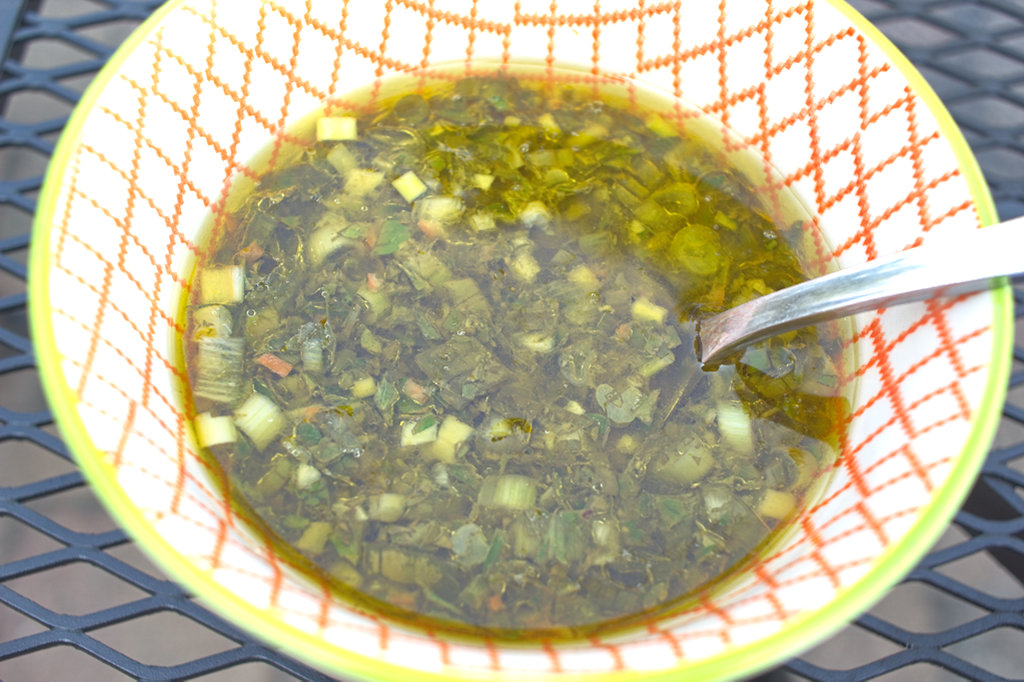

Sauce chien is sometimes called sauce creole in Guadeloupe but I’ve more often seen it referred to as sauce chien. This translates literally as “dog sauce.”

It is important to note at this time that there is no dog in this sauce, it is not considered fit for dogs nor is it fed to dogs, at least to my knowledge. There is a particular knife brand well-known in the French Caribbean called Chien, or Dog knives. The sauce, made up of minced onion, garlic, parsley, Scotch bonnet chili, lime zest and salt soaked briefly in a small amount of boilingwater and then dressed with lime juice and olive oil, is named after these knives as they were commonly used to prepare it. It is very much like a wetter, spicier, bright and tropical chimichurri. It is delicious.

Back to the Sandwiches

Once again, this sandwich consisted of chicken, sauce chien, Matouk’s hot sauce, lettuce, tomato, and onion. It was good, but overwhelmed by the flavor of the Matouk’s. I resolved to leave that off in the future.

Next we tried the saltfish, and I made the mistake of choosing the largest, most balloon-like of the rolls and completely filling its cavity with the shredded fish.

This was a massive amount of fish, and completely overwhelmed not only the other ingredients of the sandwich, but the bread itself. The sandwich quickly got out of hand and had to be finished with forks. The fish was great though, and the bits with some sauce chien attached even better.

The bread itself, fried as it was at a temperature between 325° and 350° Fahrenheit, was sturdy enough, with a thin crisp and non-greasy outer coating and a crumb that , beside the one big open central hole, was fairly tight. It’s just that I overloaded this sandwich. I vowed to get it right with the conch bokit.

And I did. I dressed the salad side with the sauce chien this time, to give the camera a better look at the conch. Some of it was still quite chewy, despite the time it spent in the pressure cooker. The flavor was wonderful though, delicate and mildly sweet in the way some shellfish are, and the sauce chien, onions, tomatoes, and lettuce only enhanced that flavor, rather than stepping on it.

The central cavity of this particular bokit had left a particularly thin layer of bread on the bottom, so I inverted it to help contain the conch meat better, making for a strange looking but sturdy and delicious sandwich.

Day Two

I had a few more things I wanted to try with these Guadeloupean fry breads, so the next day I made a second batch. This time I used the recipe from the Ketty Kreyol page, which used a hydration ratio of 67% and was thus a stickier but more malleable and workable dough. This made a notable difference in the result when frying.

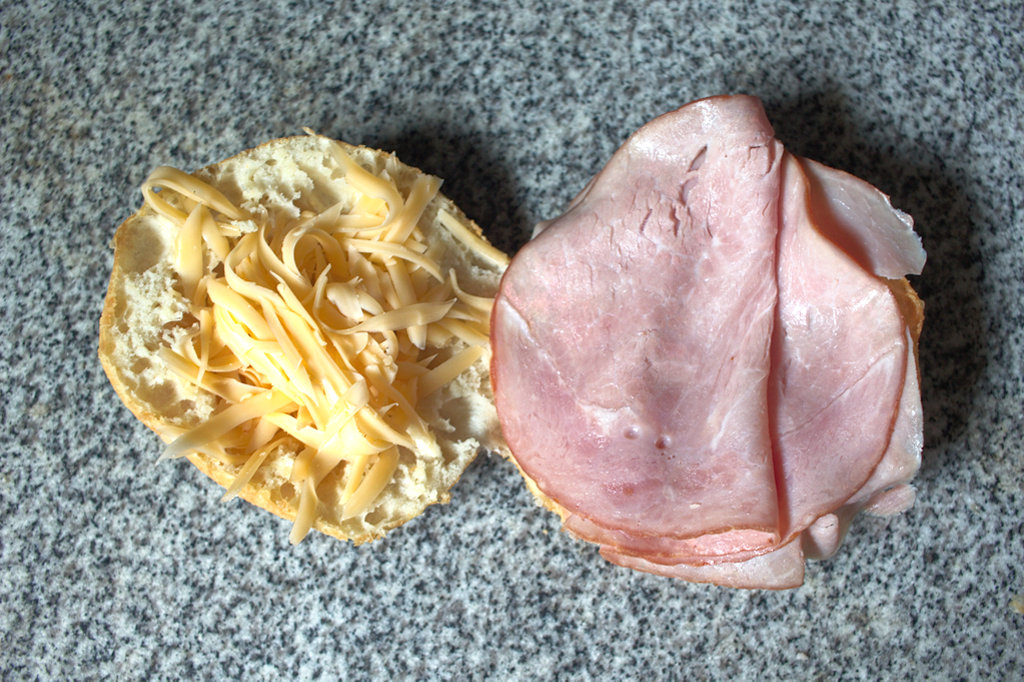

While there was still a central cavity from the rapid expansion of the dough in the heated oil, the more open hole structure of the better-developed dough made that cavity smaller, its edges less well-delineated. The bread was softer, but still sturdy due to the crisp outer shell. Rather than frying them all at once, I made the first one and immediately stuffed it with ham and shredded Gouda, hoping that, as Ketty Kreyol described, the residual warmth from the fryer would melt the cheese.

It didn’t, not really. But it softened the cheese, and cupped it in place, and made for as good a ham and cheese sandwich as I’ve had in a while. Surely better than the Hardee’s Hot Ham and Cheese whose praises I’ve sung in the past.

The bread comes together in a couple of hours, and if deep-frying things wasn’t such a pain I could see this become a weekend breakfast staple for us. I suppose I should learn to make English Muffins instead.

I also used this second batch of bread to give the saltfish a second chance. I was almost out of sauce chien, so I took what I had left and stretched it by mixing it with mashed avocado. This, I will be making again soon.

Perhaps not the saltfish–though maybe I will, since I’ve found a reliable source for it and I have come to enjoy the flavor–but the condiment. The bright herbaceousness of the sauce chien is a perfect seasoning for the fatty fruitiness of the avocado. There’s lettuce in there too, and it’s doing its part, which is mostly to provide a little crunch and moisture, to keep the sandwich from being all fish and bread.

This was perfection, Mindy’s favorite of the weekend and my own. I tried this combination again with the chicken.

This was good as well, but the chicken flavor did not match up to the sauce chien quite as well as the saltfish had.

At the end of the day, a bokit is a fry bread, like many others. Fry breads are a cheap and durable source of calories for a number of cultures, a worker’s food that can be slipped into a pocket or satchel and consumed during a day’s labor. They are usually filling, if not delicious on their own. However, the Guadeloupean twist on fry bread that makes their bokits suitable for stuffing as sandwiches also makes them an ideal street food.

I like sandwiches.

I like a lot of other things too but sandwiches are pretty great

Recent Comments