The Ploughman’s Lunch

The Ploughman’s Lunch, a phrase popularized as part of a campaign by the UK’s Milk Marketing Board to get a post-WWII England to get back to the cheese-eating, is yet a legitimate piece of the English past. A simple cold meal of bread, cheese, pickles and beer, a ploughman’s lunch of today is a demonstration of food preservation techniques that can be traced back hundreds and thousands of years through human history. Salting, smoking, curing, drying, pickling, fermenting, even cellaring, all these are methods of making foods not only less susceptible to rot, but to impart a desired flavor and texture that is longer lasting than the fresh food itself would be.

The fact that bread, cheese, pickles and beer make a convenient and portable lunch to be consumed at midday while perched on a pile of rocks at the edge of the field you’ve been working all morning is a testament to the lasting power of those ancient techniques. The fact that it makes a convenient way to consume some calories while perched on a barstool at your local is a testament to their enduring tastiness.

Se BeÓr (the beer)

Not unlike the other preservation techniques I’ve mentioned, brewing is not only a method of producing a tasty alcoholic beverage, but also a method of preservation, not of grain per se, but of water. By fermenting the malt sugars in a solution of water, the brewer introduces benign fungi in the form of brewer’s yeast, which consume those sugars, converting them to alcohol and carbon dioxide. A thriving colony of yeast, along with even the small concentration of alcohol present in a medieval ale, was enough to suppress the bulk of other harmful microorganisms that could be present in the water.

The use of hops as a further preservative in beers caught on in other parts of Europe between the 9th and 12th centuries. In England, however, brewers stubbornly continued to draw distinctions between “beer” made with hops, and true ales, made with the traditional combination of herbs and spices called a gruit. It wasn’t until the 18th or 19th century that the use hops overtook that of gruits in English ales.

Before I began my deep dive down the rabbit hole of sandwiches a few years ago, I was a pretty avid homebrewer. I still brew the odd ale once or twice a year but don’t pursue it with the intensity I once did. Still, I felt up to the task of brewing a medieval-style ale for this post.

By medieval style, I don’t necessarily mean an open-cask natural lactic fermentation, poor sanitation, and a sour mess of a beer necessarily. I don’t even mean using the most authentic ingredients for a gruit. But throwing together a little bit of what I had on hand, with a little bit of what was easy to find at a nearby homebrew shop (Bev Art on the south side of Chicago, who’ve recently moved and are now sharing premises with Wild Blossom Meadery under the same ownership), I put together a decent recipe. It used Maris Otter, a rich English malt, along with brown malt and toasted oats, a small amount of stale hops for the preservative qualities, heather, ginger, and thyme for the gruit, and Lallemand Windsor yeast, producing a low-alcohol mild ale, savory and grassy with a slight peppery kick, yeasty to the nose and fruity on the palate.

The packaging for the beer wasn’t exactly medieval either, but who’s going to argue with this happy tap handle?

Se HLAF (the bread)

Baking itself is not necessarily a method of food preservation, but it is a method of taking preserved foodstuffs in the form of grains, kept isolated, dry, and relatively unoxidized by storage in silos, and transforming them into edible and delicious works of art.

The brewing of beer and the baking of bread went hand-in-hand in medieval times in England. A medieval brewery would have used naturally occurring yeasts to ferment its ales. By concentrating the sugars of malted grains in their worts, they were able to cultivate those yeasts into a form that was usable by bakers for quickly leavening breads. Bread in medieval England was usually leavened by “barm,” called Kräusen in German brewing; it’s the foam of active yeast that develops on top of fermenting beer. That foam can be skimmed and used to begin fermentation on a new batch of beer or, in this case, a starter for a loaf of bread.

The bread of the middle ages in England often used barley or rye instead of or in addition to wheat, was often milled less thoroughly than modern flour, and might contain nuts, seeds, or dried fruits in addition to the grain. In designing my recipe, I took these facts into account, but also wanted to make something with a nice soft crumb and hole structure, that would be tasty (and, let’s be honest, would photograph well for the website). I think I did pretty well, though when I was calculating hydration I failed to take into account the fact that the spent grains I used in the dough as well as to top the bread were still quite wet. My dough was very loose and sticky, and I had to add quite a bit of bread flour to the mixer and then work it quite a bit after the first rise on a very well-floured surface before I could get it to even vaguely retain its shape. Next time I’ll dry the grains in the oven first.

A Brewer’s Bread for a Ploughman’s Lunch

Ingredients

- 200 g starter see notes below

- 50 g rye flour

- 100 g whole wheat flour

- 200 g bread flour

- 2 Tbsp honey

- 1 tsp yeast

- 2 tsp salt

- 260 g water

- 150 g spent grains + more for topping

- 1 egg white beaten with a bit of water

Instructions

- Combine the starter, flours, honey, yeast, salt, and water in the mixer and mix on low with the paddle until the mixture comes together.

- Switch to the bread hook and knead, adding more bread flour until the dough is workable. Knead for 5-8 minutes on medium.

- Transfer to an oiled bowl, cover with a damp kitchen towel and let rise until doubled, 2 or so hours.

- Work on a floured surface with a bread knife, tucking under and shaping and adding flour until you get something resembling a ball.

- Transfer to a very well-floured 9″ banneton, seam-side up, cover with the damp kitchen towel and allow to rise for another hour, until the dough has reached the top of the banneton.

- Preheat oven to 450˚F with a baking stone on the middle rack and a cast iron pan on the lower rack during this time.

- Remove the towel, cover with parchment paper to invert onto a baking peel. The dough will spread out a bit.

- Brush with the egg white wash and sprinkle with the remaining spent grains, then use a lame to score an X shape in the top of the dough.

- Carefully use the peel to transfer the dough, parchment paper and all, onto the baking stone, mist the sides of the oven with a few squirts of water, and throw a half cup of ice into the cast iron pan.

- Bake for about 35-40 minutes or until the bread feels hollow when rapping a knuckle on it.

Notes

- Starter: 50/50 mix by volume of actively fermenting beer with all-purpose flour, left to ferment for a few days and fed once about a day before bake time.

The resulting bread has a beautiful dark crust with a moist, light, and well-textured crumb. It has kept much better than white breads I’ve baked, which are generally stale the next day. I’m still eating this bread 5 days later.

Se Cýse (the cheese)

Cheesemaking is among the most ancient of food preservation methods, and has likely been around as long as humans have kept herds of milk-producing animals. Akin to the type of fermentation used in brewing, making cheese involves bacterial fermentation, introducing a culture of benign microorganisms into a nutrient-rich environment–fresh milk–in order to control the spoiling of the milk and produce a delicious result.

Various sources I’ve read cite Cheshire as the oldest type of cheese in England. Those sources usually also cite Cheddar and Stilton in the next sentence. I was not able to find any Cheshire cheese, but this Huntsman cheese, layered with Double Gloucester and Stilton, was a salty, sharp shock to the senses, making the sharp well-aged white cheddar I served it with a bit of an afterthought.

Séo Butere (the butter)

The thing I like about Kerrygold butter is that there’s nothing really fancy about it. Most of the butter I can buy in a grocery store these days is very white in color, bespeaking modern efficient dairy processes. The yellower color of some butters often means more natural processes and better-fed cows. Who knows, maybe Kerrygold simply adds a little turmeric to get that color. But it’s good butter regardless, and bread needs butter.

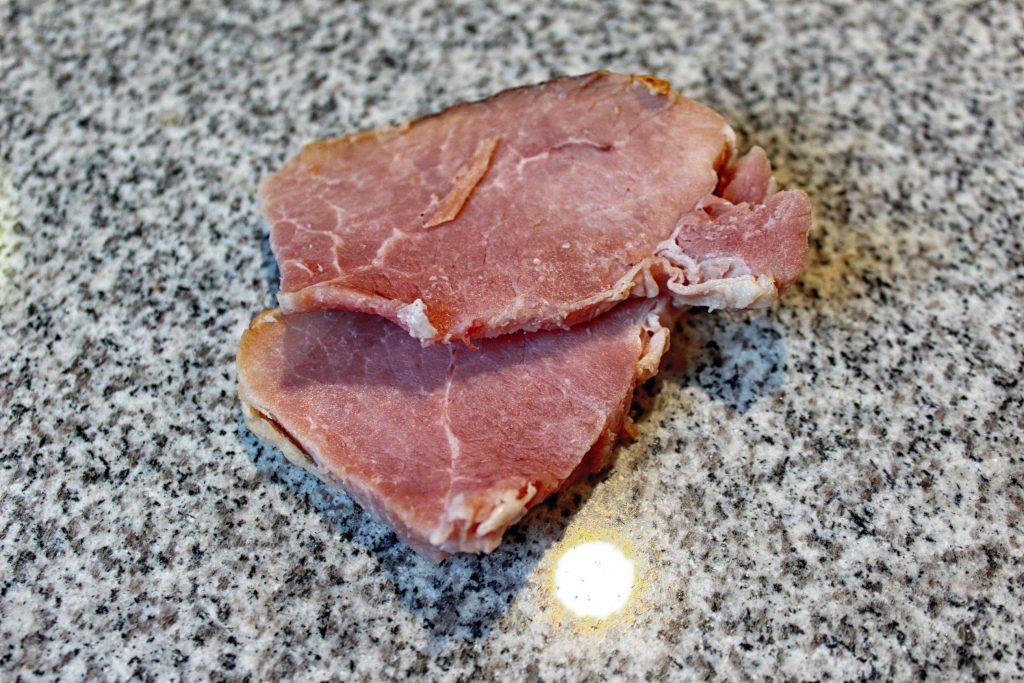

Séo Flæscsand (the meat)

Meat is not always included in the Ploughman’s Lunch, but I felt a bit of ham would not be misused here. Ham is one of the simplest and oldest forms of preserved meat, demonstrating multiple forms of food preservation, whether salted and dried, like the prosciuttos of Italy or the country hams of the southern US, or cured and smoked, like the city ham I used here. In fact, these slices were Easter leftovers, showing the power of ancient food preservation techniques (especially when combined with modern refrigeration). This was not the best ham I’d ever had, but a spectacular ham would have been somewhat superfluous in this company.

Se Pikkil (the pickle)

Finding the kinds of food a medieval peasant might have eaten on the side of a road or a field while going about his work day is a fool’s errand. The thing about the middle ages is that if you were educated enough to read a book, much less write one, you were likely of the gentry and used to finer things than those working your fields.

These days, a Ploughman’s Lunch might use a ploughman’s pickle such as Branston brand (as in the Cheese and Pickle sandwich previously covered on the Tribunal) or other chutnies as a zesty condiment for their bread and cheese mashup. I found this medieval recipe, which uses exotic enough spices that it likely never made its way to a peasant’s lunch, on a website about medieval cooking called Gode Cookery. The page provides the original text of the recipe from a 14th century collection of recipes called The Forme of Cury. It describes a mixed pickle of cabbage, fruit, and root vegetables, preserved with spices in honey, wine, and vinegar. It is likely a spiritual ancestor of modern day mixed pickles like the Branston pickle, piccalilli, or chow chow in the southern US, and represents a mixture of pickling, sugaring, and canning techniques.

Þæt Henneæg (the egg)

Pickled eggs may not have a history stretching all the way back to the fields of medieval England, but it is true that eggs were once a seasonal food, laid by hens only during warmer months (months that actually would coincide with those months the fields were being worked by said ploughmen come to think of it). A simple boiled egg is preserved enough to be put into a sack, unrefrigerated, and eaten a couple of hours later, but these pickled specimens will still be edible months from now.

They will not still be existent months from now as I’ve been noshing on a few here and there while sitting at the bar watching Netflix the past week or so, but if they were, it’s a cinch that you could eat them.

Séo Ciepe (the onion)

Pickled onions are often included in a contemporary Ploughman’s Lunch, but the simple unpickled, wrinkly little yellow onion is itself a food preservation success story. In medieval times, onions were kept in cool dark locations called root cellars, along with turnips, carrots, and other root vegetables. Vegetables like this still retain some of the self-preserving qualities of a living plant for a long time after being pulled from the earth, which allows them to be kept in these conditions for months at a time without decomposing (or further developing and growing). The natural conditions of these cellars–temperature, humidity, low light levels–were ideal for preserving these foods. A plain onion or leek was often the zestiest part of an English peasant’s meal.

Se Æppel (the apple)

Apples are also a cellarable food, though not kept with the root vegetables. I’ll be honest though, a medieval English peasant’s gnarly little apple wasn’t going to cut it for me. Braeburns, a tart and crisp New Zealand cultivar, are my favorites, and this is the apple I was going to eat.

Se Disc (the plate)

In the middle ages, a field worker’s meal might just be pulled from a sack and gnawed out of hand. A noble’s meal in those times would be served on trenchers made of bread, which were often tossed to the dogs or the poor after soaking up the juices of the meal. Eventually, trenchers gave way to plates made of wood or metal, and a Ploughman’s Lunch at a modern pub is as likely to be served on a cheese board as a plate. I’ve split the difference here by buying a basswood plank intended for carving then staining it with Danish oil and waxing it until it was sealed well enough to serve as a vessel for food.

Séo Middægþénung (the luncheon)

Lunch was served (for dinner) on a slab of wood, with thin slices of apple and onion arrayed in one corner of the plate and cheeses, ham, egg, and pickle on the other, the buttered bread between. The beer was served at cellar temperature, lightly carbonated, in a pewter mug.

As this is a sandwich website, I eschewed the Guardian’s exhortation not to construct a sandwich from the fixings. The bread, along with some of each cheese, the mixed pickle, some ham, apple, and a few rings of onion, made a fine one. Mostly though I’d eat a little of this, then a little of that, along with a bite or two of the buttered bread.

The mixed pickle was sweeter than I’d anticipated–likely I should have used a strong malt vinegar rather than the cider vinegar I opted for, but it’s a tasty treat regardless and the recipe gave me three 24oz mason jars and one pint jar so it’ll last me a while. I can’t say enough good things about how delicious this bread is, and I’ll work on refining the recipe so that it holds its shape better. In my previous attempts at pickled eggs, I’ve always tried to make them too spicy and ended up not enjoying them as much–since chili peppers would not have been a thing in medieval England, these eggs are much more approachable, and are washed down spectacularly well by the light, yeasty and fruity ale, the savory peppery notes from the thyme and ginger generally in agreement with the pickling spices while the heather provides a pleasant and appropriate grassy backdrop.

Bread and butter, cheese and apple, salty ham and sweet pickled carrots, the meal is a series of complementary contrasts that tradition has handed down to us. And it’s the perfect thing to eat while quaffing a few brews. I can’t say that the Ploughman’s Lunch should be considered a sandwich–and in fact it has been removed from the Wikipedia List, though we elected to cover it here anyway–but I’m happy we tried it.

I like sandwiches.

I like a lot of other things too but sandwiches are pretty great

I found this to be an entirely delightful entry, Jim. Great work!

A ploughman’s sandwich in the uk (sold in supermarkets and pubs is generally “granary” bread, cheddar (or Red Leicester), tomatoes, lettuce and Branston type pickle. You might see ham, egg or apple added in a fancier pub version