Katsu Sando

Like many eastern Asian countries, the staple grain for Japan throughout its history was always rice. Wheat, though known and used, was rare, and bread was only introduced after contact with European traders. The Japanese word for bread, pan, might make you think it came from the Spanish (pan), or the Italian (pane), or even the French (pain), but it was actually the Portuguese (pão). There are in fact a large number of Portuguese loanwords in Japanese. Portugal was the first European country to make contact with Japan, back in the mid-16th century, and bread was among the products (and pan among the words for those products) that they introduced. Less than 100 years later, Japan isolated itself from European influences, and prohibited the consumption of those products, an isolationist policy that lasted for 2 centuries. However, those words remained part of the language.

Bread-based snacks (such as anpan, a kind of roll stuffed with sweet red bean paste, and other pastry-type confections) became popular in Japan after their isolationist period ended, but it wasn’t until the post-WW2 occupation of Japan by the US that bread in general became a staple of the Japanese diet. Even after the occupation, the governments of the US and Japan produced propaganda to encourage people to consume wheat instead of rice; Japanese school lunches in the 1950s consisted of bread made from the wheat flour and milk powder provided by America. Since that time, the consumption of rice in Japan has trended downwards while the consumption of bread (and other wheat-based foods like noodles) has trended upwards.

Day-to-day slicing, toasting, and sandwich-making bread in Japan is called Shokupan or “eating bread.” It’s a very white, very soft, very square loaf with a plain crust that is often cut off and used to make panko. Sometimes it’s sliced thinly, sometimes it’s sliced quite thick. Sometimes it’s made a little sweeter with a milk roux for something called Hokkaido milk bread (good for sweet spreads and dessert sandwiches like Furutsu Sando).

I don’t know if Shokupan is required for Katsu Sando–maybe I’d be able to get away with plain old American squishy white bread–but Tonkatsu sauce certainly is, and Kewpie mayonnaise is recommended. I also kind of wanted to try some Japanese mustard (not traditional in this sandwich, but my sinuses have been a bit clogged and I’m told this mustard is Serious Stuff). I was able to find Kewpie mayo at the Korean market we frequent but tonkatsu sauce and Japanese mustard were more difficult to source, so I took my wife to lunch at a Japanese market in Arlington Heights called Mitsuwa.

We were starved when we arrived so we made a beeline for the famous food court. My coworker Sean, whose wife Junko is from Hokkaido and frequents Mitsuwa, had advised us to go for the Shio (salt) style Ramen from Santouka but I had my eye on the Katsu curry from Densetsu No Sutodonya, and Mindy couldn’t pass up their fried chicken bowl, so we started there.

- Katsu curry (no photos of Japanese curry donuts)

- Fried chicken bowl

- Mitsuwa food court

Mindy’s fried chicken was amazing (though the rest of the bowl consisted of plain white rice and shredded raw cabbage, which didn’t thrill). Sean informs me that the way this chicken is fried is called karaage, which essentially means “Chinese-fried.” He tells it better than I do though:

Also, the chicken you liked is “kara-age”. Apparently the Japanese brought this back from China. China now calls itself

which means middle country but used to call itself by the name of whatever emperor was ruling at the time, and at the time that was brought back from China the Japanese pronunciation of the character for that ruler was “kara”. So it originally just meant “Chinese fry” I guess. This was all news to me and found out because I asked her why they call it “empty fry” (Kara usually means empty in Japanese) and received a lecture on my own ignorance. I had hitherto never thought to question the etymology of what I ate.

I enjoyed the Katsu curry, but the large strips of breaded pork were unmanageable using the plastic forks available. The breading disintegrates and separates from the meat in the presence of the curry sauce, which reminded me of a simple chip-shop curry sauce more than anything. (Don’t get me wrong–I love chip-shop curry sauce)

We also tried some things from a Tempura stand–the tempura soft-boiled egg was difficult to manage but utterly delicious, just the barest coating of light batter covering a bursting yolk–and we did share a simple bowl of salt ramen from the stand Sean recommended.

- Mitsuwa ramen stand

- Salt ramen

There were bigger servings and fancier options there, but it was a beautiful bowl of noodles, and far different from the instant ramen that is still an occasional guilty pleasure of mine. The broth was light-colored, milky and opaque, and the noodles were topped with a slice of pork, two kinds of mushrooms, scallions, sesame seeds, the obligatory slice of Narutomaki, and what appeared to be a rock-hard little cherry but was actually Umeboshi, a Japanese-style pickled plum.

After lunch we wandered around the store a bit looking for ingredients, then made our way to the in-store bakery, Pastry House Hippo, to find Shokupan. We learned that they were out and would not have more ready for at least 90 minutes, but I picked up some “Danish Shokupan,” less pure white than the regular Shokupan, and with a more interesting, less fluffy texture. We also found that they sold premade sandwiches from a refrigerator case, including the Katsu Sando I was there to investigate.

- Katsu sando in Pastry House Hippo

- Yakisoba Pan I presume

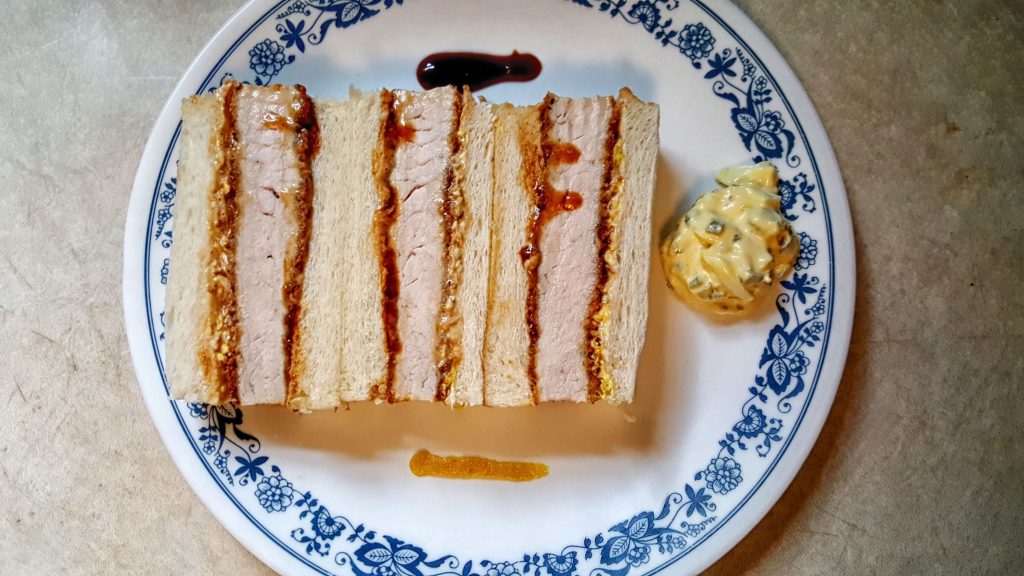

- Katsu Sando

- Furutsu Sando

- Danish shokupan from Pastry House Hippo

The Hippo version used a very thin cutlet of pork, which had been coated in tonkatsu sauce to the point where its breading had lost all texture. Perhaps this is the nature of the sandwich, as it is generally served cold or room temperature, long after a breaded fried cutlet would be at its peak. I also appreciated the opportunity to try a “real” rendition of the furutsu sando I made last year. The apricots were a nice addition. I’m kicking myself now for not getting any of the yakisoba pan but at the time, they freaked me out a bit. There’s something sinister and a touch Lovecraftian about them, and I’ve written about my (usually less-than-great) experiences with carb-on-carb sandwiches before.

Still on the hunt for the pure white fluffy Shokupan, we went around the corner to a little Japanese bakery Sean had also mentioned called Bakery Crescent, where I not only found the bread I needed, but we also picked up a red bean paste donut and a coffee cream pastry. How we found the additional stomach capacity to eat them I’m not sure, but they didn’t survive long enough to be photographed. The bread, however, made it home safely.

With the bread handled, the tonkatsu sauce and panko bread crumbs I’d picked up at Mitsuwa (not to mention the Japanese mustard paste), and the Kewpie mayo I’d previously found at Joong Boo market, all I needed now was some pork.

- Panko bread crumbs

- Tonkatsu sauce, Japanese mustard paste, Kewpie mayo

Cabbage, too–you can’t often tell from photos, but katsu sando usually has a little shredded cabbage in it as well. I ended up using Napa cabbage as I thought it would work best raw in a sandwich but if anybody out there knows a more appropriate type of cabbage to use, I’d love to hear about it. For the pork, I first picked up some thin cutlets of pork loin at my local market, then thought better of it and bought some nice thick cutlets that I tenderized with a mallet before breading. The breading process is simple–season the meat, dredge it in flour, dip the floured meat in an egg wash, then lightly press it into a plate full of bread crumbs. In every step of the breading process, make sure you get full coverage of both sides and the edges.

- thick pork loin cutlet

- Tenderized cutlet

- Seasoned, tenderized cutlets

- Breaded with panko crumbs

I fried these a single time, 3-4 minutes each side, in about 3/4″ of oil. After the fact, I got some frying advice for katsu sando via Sean. Apparently the proper way, much like with French fries, is to fry the cutlets twice, once to cook them (almost) through and a second time to crisp up the surface.

Was relaying your adventures in Japanese cuisine over the weekend to my wife just now. Asked her about the whole frying the pork twice thing and she said “we’ll you’re supposed to but I don’t always because I’m lazy.” When pressed on the issue she said the proper way is to first fry it at a lower temp for longer then pull it out when the meat is probably still mid rare and rest it. It will cook through to done while resting. Turn the heat up and put it back in for a short time. Apparently this second dip makes the outside crisper and less oily because the oil doesn’t stick as much when it’s hotter…

The best part of this story is when I asked her about the oil temps. How hot is “low heat”? And she said you know… Low heat! [More prodding…] When the chopstick goes like “potsun potsun” and this is one of those Japanese words I cannot translate. I believe they are called onomatopoeia. The Japanese love those. There’s no equivalent for most in English. Needless to say, she measures all her oil temps by how a wooden chopstick reacts when stuck in the oil for a few seconds. More specifically how rapidly the bubbles form on it. Bigger, slower bubbles equals low and smaller more frequent bubbles equals high. And she told me this in kind of a duuh don’t you know anything manner. Maybe (probably?) everyone knows this stuff and I’m the idiot but I found it amusing that she has never even considered the prospect of actually measuring oil temperature.

So I didn’t use the twice-frying technique, and the pork I used was probably way too thick even after being pounded out (though I think thinner cutlets would get lost in these thick slices of bread), but I’ll be damned if the cutlets didn’t look beautiful coming out of the pan.

Katsu sando are generally served cold or room temperature, so I let the cutlets cool for an hour before continuing.

Assembly

We start with two slices of shokupan.

Add a little kewpie mayo to each slice.

Put some shredded cabbage on one side of the sandwich.

Apply tonkatsu sauce to both sides of the cutlet and place it atop the cabbage.

Then assemble the sandwich, cut off the crusts (I know, I know, we’ve come a long way since the club sandwich days when I considered cutting off crusts to be “unbearably twee”), carefully slice the sandwich into three rectangles and arrange them cut-side-up in a row. I served the sandwich with an extra squirt of tonkatsu sauce, some Japanese mustard, and a scoop of a Japanese-style egg salad that I made.

This sandwich is incredible. Tonkatsu sauce is reminiscent of British HP sauce (and similar brown sauces) or a sweeter A1, that malty/salty, sour and sweet combination that works so well on meats. Kewpie mayonnaise is richer, saltier, and more tart than most store-bought mayonnaises in the US, and while the Shokupan appears to be very similar to plain old squishy white bread, it is maybe a bit denser, firmer, able to retain its shape, and less prone to disintegrating in a juicy, saucy sandwich like this. The cabbage takes a back seat, adding a bit of a flavor accent without contributing much texturally.

That mustard, though. I had had a bit of a cold in the week leading up to this sandwich. That mustard cleaned me out. You know that good chemical-burn type hit you get from a good strong horseradish or mustard or wasabi? This had that in excess. I had to find a way to incorporate more of it.

Beef

I still had a half-loaf of Danish shokupan that had yet to be used, and a whole lot of mustard. According to the Wikipedia page on Tonkatsu, alternative forms of katsu are sometimes made using chicken, ham, ground beef, or steak. Why not try a sandwich made from a less delicate meat, that would stand up better to a good hit of that fiery mustard?

I decided on cube steak, tenderized with a mallet, breaded and fried with a method identical to that I’d used for the pork (the beef only went 2 minutes per side though).

- Breaded, tenderized cube steak

- Fried cube steak

I assembled the sandwich the same way, with the additional step of spreading a good amount of Japanese mustard on the side opposite the cabbage.

I sliced off the crusts and presented the sandwich in much the same way I’d done with the pork.

You can see the more interesting texture and yellower color of the Danish shokupan compared to the normal bread for this sandwich. The steak was less juicy than the pork, but had a more aggressive flavor that stood up better to the mustard. That mustard was the star of this sandwich though. It combined with the tonkatsu sauce and the kewpie mayo to make a supersauce that could likely not be replicated by simply mixing the three. I’ll be looking for ways to use this stuff whenever the weather has me sniffling.

Still, there’s no contest here. The pork sandwich was outstanding, mustard or no, and I appreciated it all the more having only applied the sauces at the last minute, so that the breading retained most of its texture. I suppose if I’d used the twice-fried technique Junko described, it might have been even crisper. I appreciate Sean and his wife so much for the insight they’ve provided. He warned me though:

Disclaimer: I’m only good at eating food. I know little about cooking. What I do know is anecdotal. When I have to cook the kids get grilled cheese. No sides.

If the internet calls you an idiot, well, you have been warned. Haha.

So let me know, those of you who are more familiar with katsu sando: how did I do?

I like sandwiches.

I like a lot of other things too but sandwiches are pretty great

You’ll be glad to know that Napa cabbage was exactly the right kind of cabbage to use, since that’s the kind of cabbage ubiquitous in east Asia.

I’ve been to Japan many times and had katsu sando everywhere from convenience stores to bullet trains. Yours looks good to me. I have to say that I’ve never had one with enough mustard to even notice though.

Oh? Kewpie mayo is saltier? I’ve always heard that’s it’s (unneutrally) sweet 😮