An Edible History of the Club Sandwich

A Turkey Sandwich Wearing a BLT Hat

That’s what club sandwiches have always seemed like to me. It’s like this, you’ve got a turkey sandwich

So you think to yourself, this turkey sandwich kind of sucks. What is an actual good sandwich?

So maybe, if I want this turkey sandwich to be less boring, I could just somehow add a BLT to it, right?

That’s a whole damn lot of bread though. What if we took away one of the middle slices?

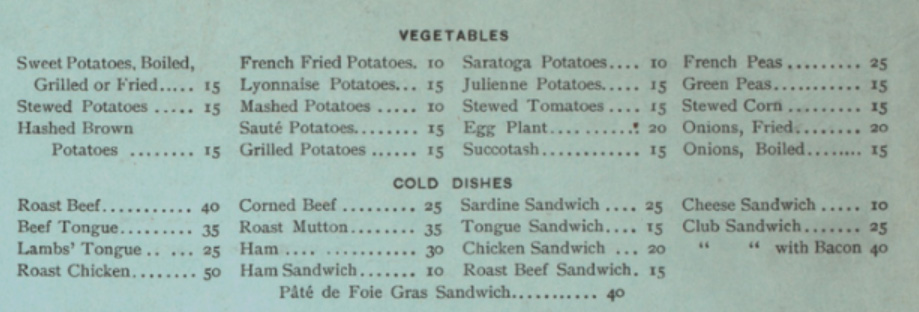

You know exactly what to expect when you order a club sandwich in America. It’s going to be sliced turkey, often of the crappy deli variety, tomato, lettuce, and bacon–sometimes they’ll use ham instead of bacon, and as much as I like ham, this makes me so mad–on three slices of toasted bread, skewered, cut into 4 triangles, and served with plain potato chips.

Sometimes they’ll do the layers like I did here. Sometimes both layers will have identical ingredients. Sometimes, when they use ham, all the meat goes in one layer and all the salad in the other. Maybe instead of chips, you’ll get a different side dish. Maybe they’ll use Tofurkey and tempeh bacon. These are pretty minor variations though. The triple-decker club sandwich is a known quantity in American cuisine.

An American Metaphor

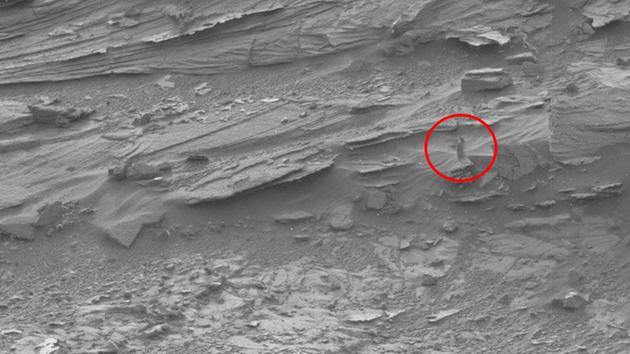

In fact, the three-slice-of-bread construction is the main visual image people associate with the words “club sandwich” in America. (It was also the visual inspiration for the Sandwich Tribunal logo, as something quintessentially “sandwichy”.) When NASA recently posted a photo of a mysterious lady-like figure taken by the Mars rover, one Facebook commenter was more interested in why she was standing on a giant club sandwich.

When Americans talk about something that has 3 or more layers, “club sandwich” is often a reference we employ. There’s the “club sandwich model” scientists are using for the oceans of Jupiter’s moon Ganymede; and the “sandwich generation” term baby boomers use to complain about having to support both their children and their parents has given way to the term “club sandwich generation,” used by baby boomers to complain about supporting their grandchildren as well.

There’s another club sandwich trope in America though. Look at the menu of just about any fast food restaurant, whether it’s a big franchised operation or a small mom-and-pop affair. If they have a “chicken club” sandwich on the menu, it basically means they took their regular chicken sandwich and stuck bacon in it. (They also tend to add Swiss cheese, but I don’t consider cheese to be an essential part of any club sandwich.)

So what is the defining aspect of a “club” sandwich? Is it as simple as adding bacon? But what about all the club sandwiches that use ham instead? Is it the multiple layers? If that were true, a Big Mac might qualify, or this excellent double cheeseburger (with middle bun) I recently had at Working Man’s Friend in Indianapolis.

Not to mention that James Beard, one of the most prominent, defining voices of American food culture in the 20th century, called the triple-decker club sandwich a “horror.”

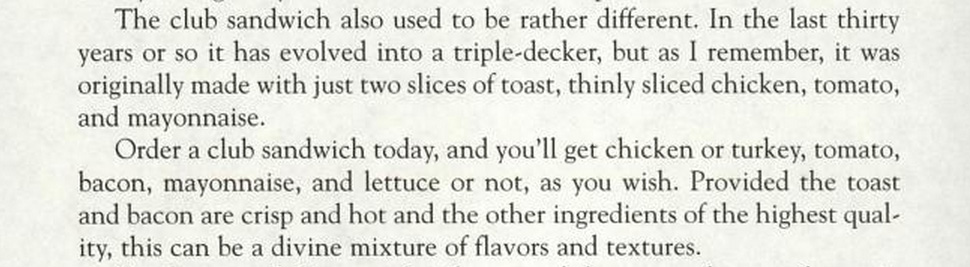

He reiterated this sentiment, though less forcefully, in his 1974 book Beard on Food: The Best Recipes and Kitchen Wisdom from the Dean of American Cooking

.

His ideal version, remembered from his youth, doesn’t even include bacon (or ham either), muddying the waters somewhat. However, I bet if you were to go and look at the recipe for a Club sandwich that he provides in American Cookery, you’d see bacon in the ingredients.

Origins

So where and how did the club sandwich come about? The most common explanation is that the sandwich originated in Richard Canfield‘s Saratoga Clubhouse in upstate New York around 1894. However, there are other references to “club sandwich,” “club house sandwich,” and “____ club sandwich” around that time and earlier.

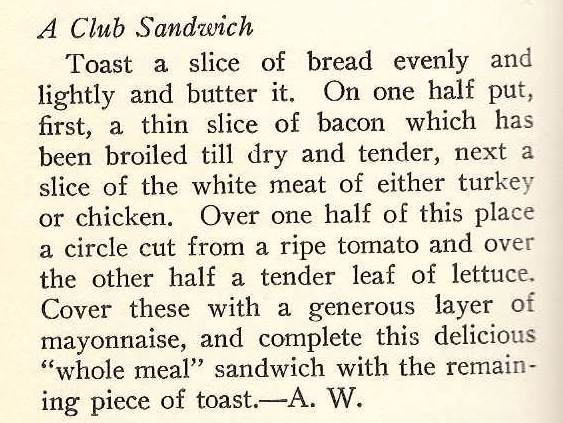

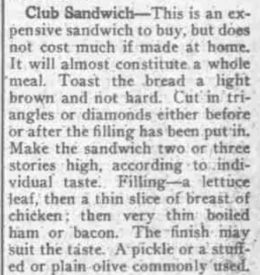

The “earliest published recipe” for a club sandwich that’s commonly cited is the 1903 Good Housekeeping Everyday Cook Book. I bought a reprinted copy just so I could show it to you. (It was on Amazon for a penny)

I find the recipe puzzling–the meat only goes on half the bread? The tomato only goes on half the meat? Where does the second slice of bread come from? Strange. In any case, this book was published by Good Housekeeping magazine and presumably gleaned from its pages–doesn’t that suggest that a recipe must have been published earlier, in the magazine itself?

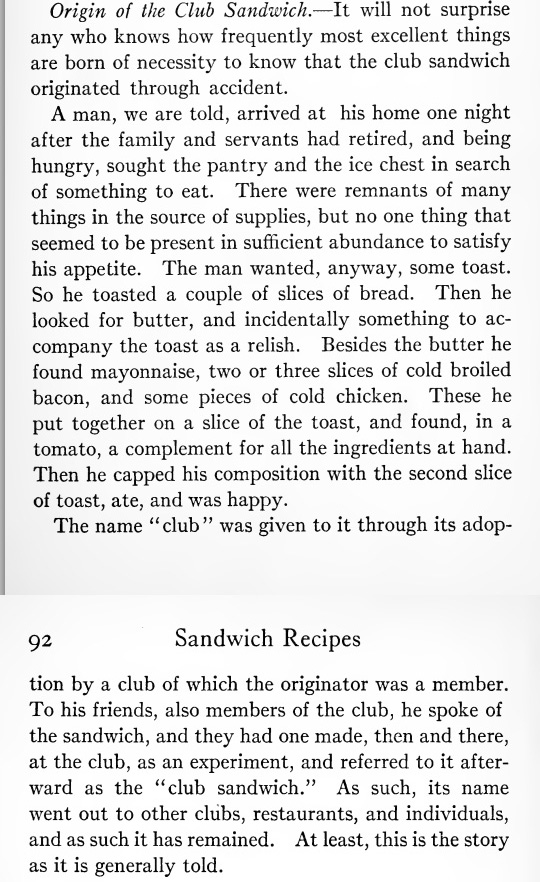

There are other origin stories, other clubs who claim to have originated the sandwich. It’s also been said that the sandwiches originated on the club cars of passenger steam trains. Then there’s the anecdote of the late-night fridge raider, such as this one from Marion H. Neil’s 1916 book Salads, Sandwiches, and Chafing Dish Recipes.

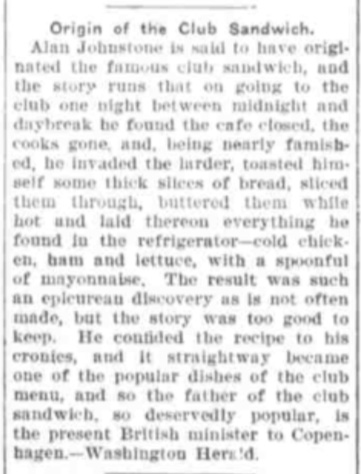

An earlier version of this story appeared in several newspapers in 1909–the earliest I found claims to have been reprinted from the Washington Herald, but I could not find the original in the archives–and gives the accidental gourmand a name: Alan Johnstone, a British diplomat of the time.

Fun stories, yes, but almost certainly apocryphal.

An Edible History

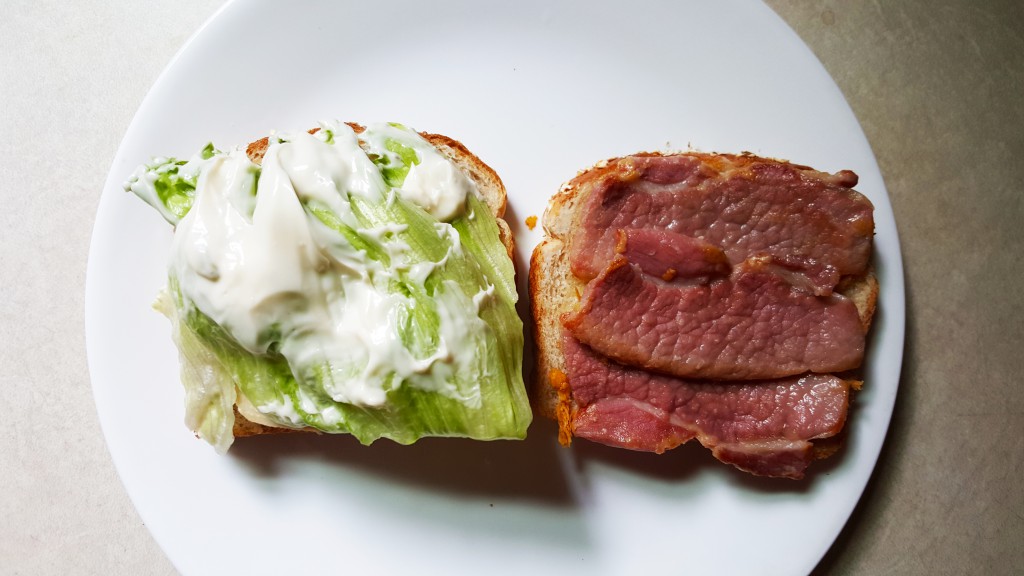

I tried the version from the Marion H. Neil anecdote and found it far superior to the bland deli version pictured earlier. I used some cold chicken breast I had roasted using this technique, which turned out fantastic and shouldn’t even be mentioned in the same paragraph as the tryptophan-flavored jello they sell in grocery store delis. Chicken, bacon, tomato, and mayonnaise on buttered toast. Everything a sandwich should be.

It was then that I decided I should probably try to prepare and eat as many unique archaic variants of the club sandwich recipe as I could find.

Some other sites I’ve read have gathered early references to the club sandwich, that have been most helpful in my search: The Food Timeline’s sandwich history, and Barry Popik’s Club Sandwich timeline, among other histories of the club sandwich. Some of my own sources have been located through these sites; some of them by searching various online archives of newspapers, periodicals, and other publications. I used the Library of Congress’ “Chronicling America” website; I used Cornell University Library’s Home Economics archive; I used archive.org; I used Google Books; I used Project Gutenberg. You’ll find links back to these sites throughout this post (usually the screencapped image itself). My own timeline is far from definitive, but represents the high points according to my own thinking regarding the sandwich.

The degree of historical authenticity I’m able to achieve will vary. Where a sandwich calls for chicken or turkey, or “fowl” in general, I’ll use the roasted chicken breast mentioned earlier, though if it specifies turkey, I’ll use the hated deli turkey. Where a recipe calls for bacon, I’ll use a thick cut applewood-smoked belly bacon I enjoy, though perhaps back bacon might be more accurate. Where it calls for ham, I’ll use some country ham I picked up on a recent trip to Tennessee and Kentucky.

For lettuce, I’ll stick with leaves of iceberg, and as for bread, I’ll mostly just use my standby oat bran bread unless a sandwich calls specifically for white or whole wheat.

A note on bread crust: many of these sandwiches call for trimming it. I wonder if this was a more necessary measure 100+ years ago, when even commercially-baked bread might have had a much harder crust and/or might have staled more quickly than contemporary commercial bread. My observant wife Mindy also pointed out the tradition of tea sandwiches, and wondered whether a sandwich served on platters in a club might not have been similarly treated. Whatever the explanation, I don’t think it’s necessary for today’s bread, and the idea of trimming the crusts off a sandwich is unbearably twee to me. There may be a day when I trim the crusts from a sandwich for the Tribunal, but this is not that day.

1880s

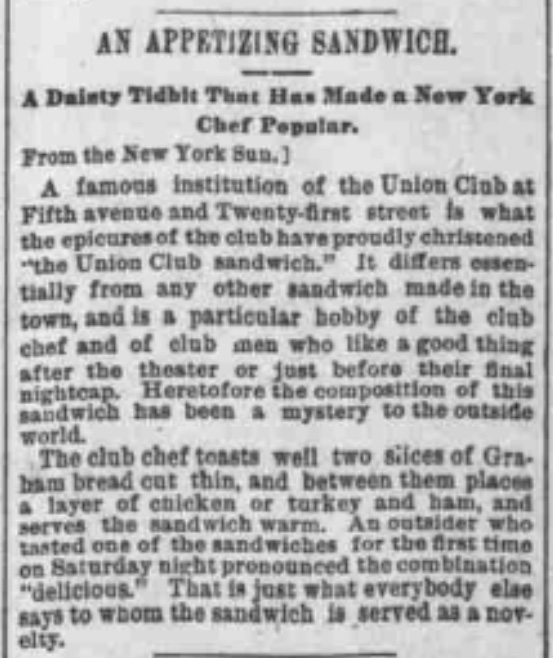

In the latter half of 1889, the Union Club in New York City had a hit with its “Union Club” sandwich. Descriptions were published in several newspapers, such as the New York Evening World

and the Pittsburgh Dispatch

and the New York Sun.

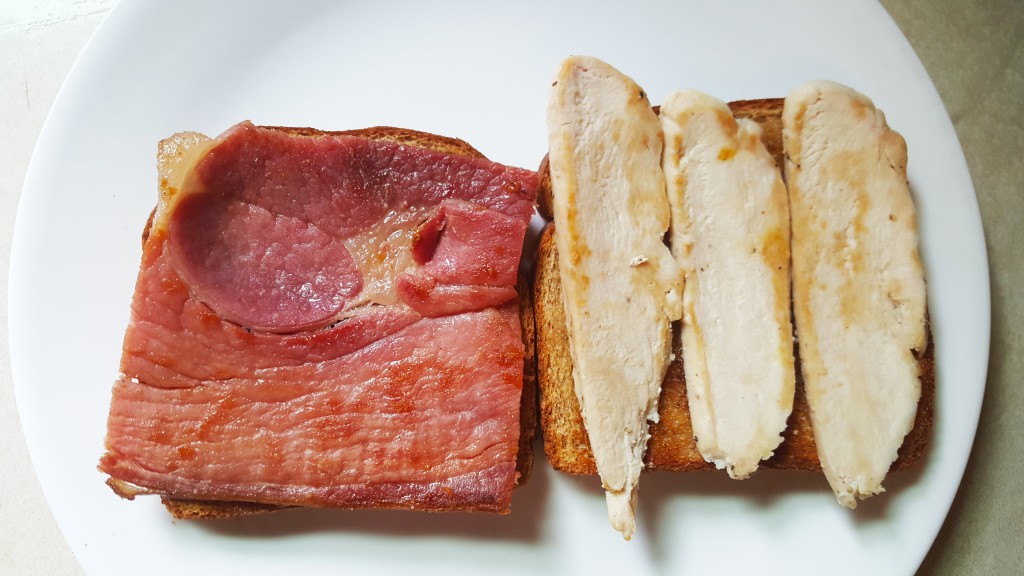

This “Union Club” sandwich consisted of broiled ham and hot chicken or turkey between two slices of toasted, buttered Graham bread. Graham bread was a high fiber whole wheat bread invented in the early 19th century as a more natural alternative to the commercial white breads of the time. I used whole wheat bread as the closest contemporary alternative I could easily find.

It may be difficult to look at this sandwich and recognize in it an early version of today’s club sandwich. But the basic combination of fowl and smoked/cured pork on toast is there. I’m not sure what the Saratoga Clubhouse sandwich looked like, as no written descriptions seem to survive. But the date commonly given for its appearance is 1894, and this sandwich predates that by 5 years.

1890s

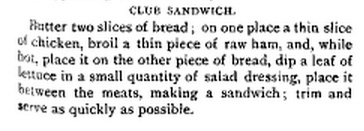

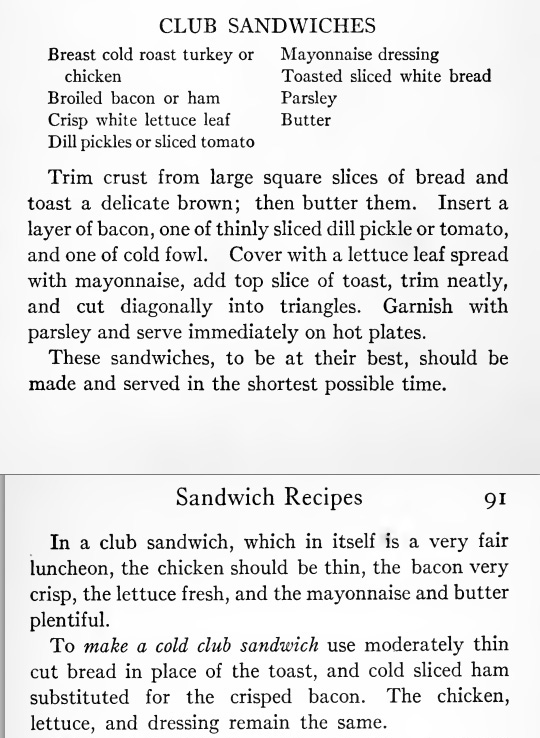

However, also in 1894, a recipe for a “Club-House Sandwich” appeared in the book “Sandwiches” by Sarah Tyson Rorer. A 1912 edition of this book is available for free on the online ebook archive the Gutenberg Project. Assuming the 1912 edition’s recipe matches the 1894 edition’s version, here it is:

Club-House Sandwiches

Club-house sandwiches may be made in a number of different ways, but are served warm as a rule on bread carefully toasted at the last moment. Put on top of a square of toasted bread a thin layer of broiled ham or bacon; on top of this a thin slice of Holland pickle, on top of that a thin slice of cold roasted chicken or turkey, then a leaf of lettuce in the center of which you put a teaspoonful of mayonnaise dressing; cover this with another slice of buttered toast. Press the two together, and cut from one corner to another making two large triangles, and send at once to the table.

People not using ham may make a palatable sandwich by putting down first a layer of cold boiled tongue, then a layer of Holland cucumber, a layer of turkey or chicken, another layer of cucumber and the slice of toast. Garnish with little pieces of water cress before putting on the last slice.

“Holland pickles” is a reference unfamiliar to me, but as far as I can tell, it’s simply a type of sour pickled cucumber similar to contemporary dill pickles.

Here we have something more similar to what I think of as a club sandwich–the familiar mayonnaise and lettuce, but with pickles in place of the tomatoes. In terms of both taste and texture, it is recognizably in the ballpark.

By 1895, a mention of “club sandwiches”–not club house sandwiches, not ____ club sandwiches–had been published in the New York Sun, though no description attended the mention, as though everyone reading should already have been aware of the particulars of a club sandwich.

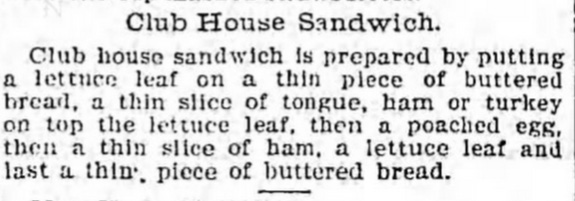

In 1897, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle published a recipe for the Club House Sandwich

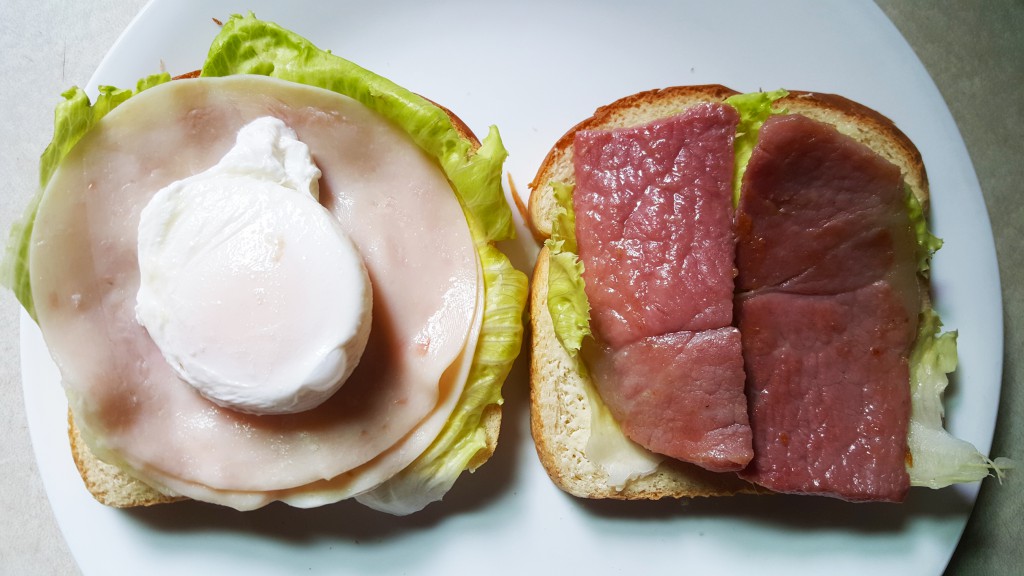

No mayonnaise here, but the poached egg serves a similar purpose. The main issue I had with this sandwich is that it does not call for toasted bread. Whether it was a simple omission or a deliberate choice on the part of the recipe writer, the untoasted bread is a mistake. Toast would stand up much better to a gushing egg yolk. I used turkey here, as I did not have tongue on hand (and a ham-on-ham sandwich seemed a bit one-note).

Also in 1897, the first mention of a club sandwich that I could find appeared in Good Housekeeping magazine. This is a different version of the club sandwich than the one appearing in their 1903 recipe book though.

In June of the same year, Good Housekeeping had published 17 salad recipes with 2 recipes for dressings–“mayonnaise dressing” and something simply called “salad dressing” that was essentially mayonnaise with a bit of sugar. I felt justified in using normal mayonnaise for this recipe.

Once again, we are hewing fairly close to the contemporary concept of the club sandwich. The country ham has a dense, chewy texture not too far off from bacon, and with the mayonnaise and lettuce this comes very close to the ingredient list of today. However, again I was frustrated by the omission of the vitally important step of toasting the bread. I feel that toasted bread must be considered an essential element of the club sandwich.

Rail

I find multiple references to railway club car versions of the sandwich from 1899. There is of course the commonly cited Steamer Rhode Island menu from October 17.

Also I have found a “Steamer Priscilla style” Club Sandwich recipe in Salads, Sandwiches, and Chafing Dish Dainties with 50 Original Illustrations by Janet McKenzie Hill, available as a free online book at Project Gutenberg.

Club Sandwiches.

(Steamer Priscilla style.)Have ready four triangular pieces of toasted bread spread with mayonnaise dressing; cover two of these with lettuce, lay thin slices of cold chicken (white meat) upon the lettuce, over this arrange slices of broiled breakfast bacon, then lettuce, and cover with the other triangles of toast spread with mayonnaise. Trim neatly, arrange on a plate, and garnish with heart leaves of lettuce dipped in mayonnaise.

Personally, I think the step of cutting the bread into triangles first and then making sandwiches is unnecessary; I’d rather assemble the sandwich whole and then cut into triangles. Otherwise, this is very much like many other sandwiches I’ve tried. It’s also the first explicit instruction to use bacon.

There are no tomatoes, there is no third slice of bread, but in terms of flavor, this is recognizably a club sandwich.

Early 20th Century

So when did the tomato and that pesky extra layer get added to the sandwich? The earliest mention of a tomato I could find–apart from the Escheresque Good Housekeeping cookbook recipe from the same year–comes in a 1903 St. Louis Republic piece about a man and his hotel lifestyle–oatmeal for breakfast, oatmeal for lunch, and a club sandwich every night for dinner.

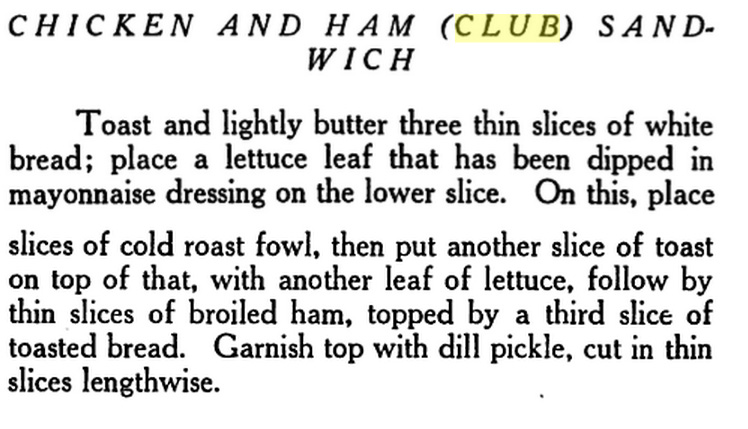

The earliest mention I could find of the “triple-decker” version of the sandwich was published in The Up-to-date Sandwich Book: 400 Ways to Make a Sandwich by Eva Greene Fuller in 1909.

This book contains numerous “club” style sandwiches–Turkey Club, Chicago Club, Boston Club, Sheridan Park Club, Club House, etc. Nearly all of them call for three slices of bread.

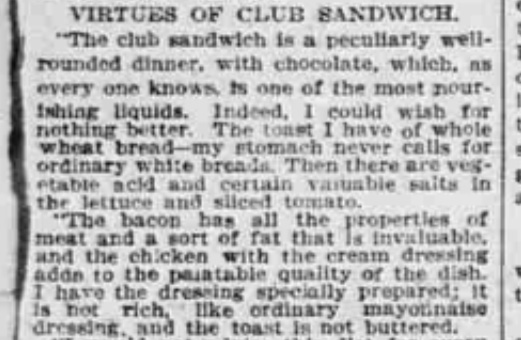

An almost identical version appeared in Chicago’s Day Book newspaper in 1912, with “three stories” optional:

I chose the Chicken and Ham Club from the Eva Greene Fuller book to try because of the strangeness of the the exterior pickle garnish and the instruction to cut it into thin strips, different than the triangles normally called for in a club sandwich. I have no idea how people make a triple-decker sandwich look nice when cut in this way.

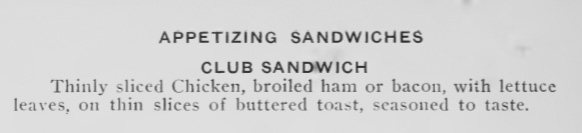

A set of bartender’s and hotelier’s guides called Jack’s Manuals published a recipe for a club sandwich in their 1910 book Jack’s manual on the vintage and production, care and handling of wines, liquors, etc. : a handbook of information for home, club, or hotel : recipes for fancy mixed drinks and when and how to serve. A brief recipe, I should add, as it’s shorter than the title of the book. Still no tomato here, or extra layer, and similar enough to others I’ve had that I didn’t bother making one.

For the most part though, by this time the club sandwich had evolved into something much like what we are likely to see served today. The 1916 Marion H. Neil book mentioned earlier does not mention three slices of bread but otherwise has all the pieces in place: fowl, bacon, lettuce, tomato, mayonnaise. Toasted bread. Though it also mentions a “cold club” sandwich where the bread is not toasted. I do not recommend.

Post-WWI and Depression-era mentions of the club sandwich are fewer but the Woman’s Institute Library of Cookery, Vol. 4: Salads and Sandwiches, Cold and Frozen Desserts, Cakes, Cookies, and Puddings Pastries and Pies published in 1928 has a very modern rendition of the club sandwich, where again the extra layer is optional (as are the tomatoes).

137. CLUB SANDWICHES.–Nothing in the way of sandwiches is more delicious than club sandwiches if they are properly made. They involve a little more work than most sandwiches, but no difficulty will be experienced in making them if the directions here given are carefully followed. The ingredients necessary for sandwiches of this kind are bread, lettuce, salad dressing, bacon, and chicken. The quantity of each required will depend on whether a two- or a three-layer sandwich is made and the number of sandwiches to be served.

Cut the bread into slices about 1/4 inch thick and cut each slice diagonally across to form two triangular pieces. Trim the crust and toast the bread on a toaster until it is a light brown on both sides and then butter slightly if desired. Slice chicken into thin slices. Broil strips of bacon until they are crisp. On a slice of toast, place a lettuce leaf and then a layer of sliced chicken, and spread over this a small quantity of salad dressing, preferably mayonnaise. On top of this, place strips of the broiled bacon and then a second slice of toast. If desired, repeat the first layer and place on top of it a third slice of toast. This should be served while the bacon is still hot. Thin slices of tomato may also be used in each layer of this sandwich if desired.

Further Studies & Minutiae

In 1930, the club sandwich was reportedly the subject of a heated debate on the floor of the US House of Representatives.

In 1931 Terrytoons made a black & white animated short titled Club Sandwich. It was retitled Dancing Mice for television. I have zero idea why it was called Club Sandwich originally, but to be fair, dancing mice was hardly a unique subject for a cartoon of the period.

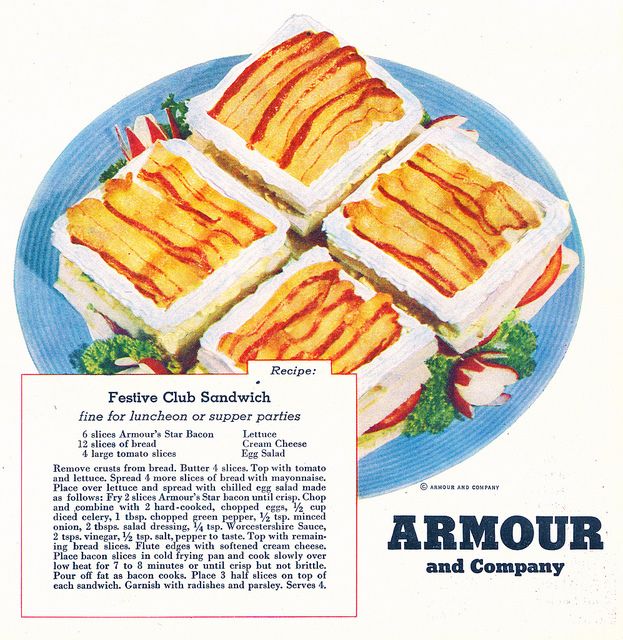

A 1944 Armour Bacon ad featured a “Festive” club sandwich recipe. The recipe included cream cheese and egg salad. Please, please don’t make this sandwich. (Though if you like that kind of wacky vintage recipe idea, you might also want to check out this club sandwich recipe from the 1960s, made with Miracle Whip and American cheese, using a tomato for the bread.)

In 1954’s holiday classic White Christmas, the characters played by Bing Crosby, Danny Kaye, Rosemary Clooney and Vera-Ellen meet up in the club car of a train and order club sandwiches.

Danny Kaye (a long-time favorite of mine) was an appreciator of good food, known in his later days as a fine cook of Chinese and Italian cuisine, and in 2013 he was honored posthumously by the Carnegie Deli in Manhattan with a namesake sandwich, the Danny Kaye Deli Club. It looks enormous.

In 1996, the MTV Movie Awards added a one-time award category, Best Sandwich In A Movie. Among the nominees was the Turkey Club Sandwich from the movie Four Rooms. Alas, it did not win.

In 2003, comedian Mitch Hedberg recorded a live album, Mitch All Together. The second track on the album, Sandwiches, features a minute long bit about club sandwiches.

In 2012, Hotels.com created the Club Sandwich Index, an economic indicator based on the average price of a club sandwich at hotels in cities around the world.

Conclusions, if any

Look, the Club sandwich is obviously a part of American culture. I didn’t need to beat you over the head with all those links for you to know that. I don’t know for sure where or how it came about (though I bet it did have something to do with all those clubs and their special sandwiches; let’s call this theory “Many clubs, one sandwich”). And I’m not sure if you necessarily learned anything from all those club sandwiches I ate, though the exercise certainly gave me a pretty good idea what they’re all about.

The main distinguishing factors of the club sandwich, to me, are 1) the combination of fowl & cured pork, 2) the toasted bread, 3) the salad in addition to the meat. I will accept ham in place of bacon, though it still annoys me. I do not, however, think partitioning the sandwich with a middle slice of bread is necessary. “That’s just a turkey BLT!” you might say. “Bite me!” I might retort.

Within those guidelines, go crazy. If you don’t like the tomato, leave it off, I think you still have a club sandwich. If you’d rather use Ranch dressing than mayonnaise, well, I think you’re gross, but it’s probably still a club sandwich. If you want to add pickles, or onions, or olives, or some other condiment or garnish, I don’t think that impacts the essential clubness of the thing. I don’t think it requires cheese either but if you want cheese, have at it.

In terms of tips for the ideal club sandwich, much of what I learned about BLTs applies. When you add your mayonnaise, remember that you’re dressing the veggies, not the meat or bread, and put it in the proper position within the sandwich, multiple times if possible. If that means you’re spreading it on the lettuce, so be it. Also, keep in mind that tomato and bacon are a magical combination and should be adjacent. Here’s a new, club-only tip–butter, melted by hot toast, can help transform the moist, mild meat of sliced chicken breast into a rich, indulgent treat.

The best one I tried so far was the simple mayo-tomato-chicken-bacon version from the origin story in the Marion H. Neil book. I can probably improve on that though. I think my ideal version, in stacking order, would be buttered toast, chicken, lettuce with mayonnaise spread on it, bacon, tomato, mayonnaise, then toast. And I’d use whole wheat, though if you’re making a triple-decker you’d probably want something a little lighter.

Oh yeah. That’s where it’s at. And as it turns out, when I finally got around to looking up James Beard’s recipe for club sandwiches in American Cookery, that’s very close to how he suggested making them.

The perfect club sandwich starts with a piece of freshly made crisp buttered toast. On this goes a leaf of lettuce and a bit of mayonnaise, slices of chicken breast, slices of peeled ripe tomatoes, a sprinkle of salt, crisp bacon rashers, more mayonnaise, and a second piece of toast. Some people toss in an additional piece of lettuce, but it isn’t necessary. Green olives and sweet pickles are standard garnish.

Hey, it’s not pandering if the guy’s been dead for 30 years.

But if you disagree with me (and James Beard)–just make it the way you like it. You’re eating it; what’s the point of eating a sandwich you don’t like?

I like sandwiches.

I like a lot of other things too but sandwiches are pretty great

Two things.

1. Really fascinating. I don’t think I’ve ever known what a club sandwich actually is and I think its most defining feature is the third slice of bread, so interesting to read that it’s a recent addition.

The thin slices thing. Reminds me of fancy afternoon tea ribbon sandwiches. Which you press before you cut, so you don’t get the falling apart thing. I’ll try to find some sandwich pressing strategies and get back to you. If I have time. The work week has now begun!

If text were bread, and Yojimbo a toaster, then the pics of bacon lettuce & fowl etc in this delicious piece would be the bacon lettuce & fowl etc of the biggest club sandwich in the world.

As Bob King saith,

“Sandwiches are beautiful, sandwiches are fine

I like sandwiches, I eat them all the time!”

Thanks for this article. I have been arguing with a restaurant here about their club sandwich. It has NO turkey on it just ham and BLT. Then the discription only says CLASSIC STYLE. I have tried to tell them they either need to add poultry or call it a ham BLT. Or at least describe it so you know what you are getting but they think I am crazy. I am going to show them this article. Thanks so much 🙂

That is bizarre. I’ve heard of places leaving off the bacon and only having ham and turkey, but just ham and bacon? I mean, could be a good sandwich but I wouldn’t call it a club.

You tell ’em this internationally recognized sandwich expert* says they’re dead wrong! 😉

* technically true, probably

How did I end up reading this entire post when I barely even eat club sandwiches? Lol, a fascinating read. I prefer bacon, tomato, lettuce, chicken, and mayonnaise, too.

One quibble that has me confused – when you refer to “decks’ in triple decked sandwiches,are you referring to the layers of filling or to the number of slices of bread?

I have also struggled with this confusing verbiage. I have sadly gone with the crowd on this one. I suppose the bread must be the decks, though one would think that the top piece of bread would be a roof and not a deck at all. Thinking it through, it makes more sense to call it a double-decker, and there are those brave souls out there who’ve flouted convention in this way, but I am a worm, and a follower, and a low uncouth man.

LOL Not sure if that cleared things up for me – but it made me laugh and that’s more than worth the confusion.

Club sandwiches are my favorite kind of sandwich ever, so thank you for the insight into their history!

I personally love turkey on them, even more so than chicken, but I can understand why chicken would seem preferable – I don’t think I’ve ever seen chicken prepared in the weird, flat, featureless slices you get with some deli turkey. Usually sliced chicken is roasted and cut directly from the breast, which is the ideal form of any sandwich meat. But all my favorite iterations of club sandwiches at restaurants do their turkey the exact same way – roasted and cut slices from a turkey breast. Roast chicken sliced thin versus deli turkey is a one-sided contest that the chicken will always win, but sliced roast chicken versus sliced roast turkey(at least on a club sandwich)? For me, the turkey wins every time, hands down.

If I have any complaint about this excellent piece, and it’s really not much of one, it’s just that I wish that the turkey had been given a fighting chance by comparing it to the chicken when prepared in a similar way, as opposed to comparing home-roasted sliced chicken breast to a blatantly inferior deli turkey product. I’m genuinely curious how well the two would compare when there’s an actual comparison to be made.

(On a completely unrelated note, the worst club sandwich I ever had was a chicken club. This hasn’t informed my preference for turkey – I’ve loved turkey clubs for years and the chicken club was a pretty recent experience – but I was shocked how tasteless it was. I didn’t taste ANYTHING but bacon – not even the bread and definitely not the chicken. It wasn’t offensive in any way; it was just the most boring, baffling experience for my tongue I’ve ever had.)

“I chose the Chicken and Ham Club from the Eva Greene Fuller book to try because of the strangeness of the the exterior pickle garnish and the instruction to cut it into thin strips, different than the triangles normally called for in a club sandwich. I have no idea how people make a triple-decker sandwich look nice when cut in this way.”

I’m really confused. Surely the intent of that line in the recipe is “garnish top with dill pickle [which is cut into thin slices]?” Not that the entire sandwich be cut into thin slices.

Hi Adrian,

It’s been 8 or 9 years since I wrote this post and I’m not sure what I was thinking. Looking back at it now, I’m guessing I thought since they mentioned using pickles or olives that the intent was that kind of old-timey olive toothpicked to the top of the sandwich. But if that were the case, then the pickle equivalent would surely be a small cornichon rather than a large pickle, and the thin slices might very well refer to the pickle rather than the sandwich. In my defense, there is some ambiguity to the phrasing but in retrospect I zigged when I shoulda zagged and I can’t defend it.

Lol no criticism intended. Great post – I learned a lot! This just jumped out at me, but none of the other comments mentioned it, so I had a moment of “am I losing it?”